Property › Confusions

George, Henry. [1881] 1930. The Land Question. Doubleday, Doran, & Co.: New York.

[52] In the every nature of things, land cannot rightfully be made individual property. This principle is absolute.

[53] The only true and just solution of the problem, the only end worth aiming at, is to make all the land the common property of all the people.

[75] Until we in some way make the land, what Nature intended it to be, common property, until we in some way secure to every child born among us his natural birthright, we have not established the Republic in any sense worthy of the name, and we cannot establish the Republic.

Green, Thomas Hill. [1881] 1888. “Liberal Legislation and Freedom of Contract” in Works of Thomas Hill Green, Vol. III, edited by Richard Lewis Nettleship. Longmans, Green, and Co.: London.

[372] If I have given a true account of that freedom which forms the goal of social effort, we shall see that freedom of contract, freedom in all the forms of doing what one will with one's own, is valuable only as a means to an end. That end is what I call freedom in the positive sense: in other words, the liberation of the powers of all men equally for contributions to a common good. No one has a right to do what he will with his own in such a way as to contravene this end. It is only through the guarantee which society gives him that he has property at all, or, strictly speaking, any right to his possessions. This guarantee is founded on a sense of common interest.

Smith, John Brown. 1881. The Brotherhood of Man. J. B. and E. G. Smith: Massachusetts.

[13] All property shall be owned by the Brotherhood of Man in common and paid for by the interested individuals, families, homes, and communities or continental brotherhoods of man, in accordance with His principle of voluntary contribution or assessment in proportion to the ability of each individual, family, home, community or continental brotherhood of man…

George Harwood (1845 – 1912) was a British businessman and Liberal Party politician. In Parliament he took a keen interest in issues regarding the Church and licensing. He was also concerned with working conditions, being a principal supporter of a bill for the early Saturday closing of textile factories.

Harwood, George. 1882. The Coming Democracy. Macmillan and Co.: London.

[268] Property is based upon social convenience, and its ‘rights’ must be governed by that; as are ‘personal rights,’ which seem much more radical: for if a man has a right to anything, it should be to his own person, yet the law does not allow him to dispose of this, in marriage or otherwise, according to his own unlimited will.

Mackenzie, Malcolm. 1883. “The Ethics of Political Economy,” The Celtic Magazine 8: 214-228.

[215-216] Property is a belonging, and by natural instinct man in his rude state does not recognise any property as sacred except what has been appropriated by labour. The English language makes this broad distinction, for all unenclosed land is termed ‘common,’ as opposed to ‘sacred.’ … Then, whatever is the produce of labour is a belonging, and whether in land or in moveable property is regarded as sacred to him who bestowed the labour, or paid the wages of labour to the labourer. Hence, it should follow, that property in land upon which no labour has been bestowed, is, by natural instinct, and by the English language, common property.

It will be admitted by everyone that the produce of labour is property. But land is not the produce of labour, but the gratuitous gift of God. Therefore, it is not property in the sense of the word which renders property sacred. … I am no Socialist in any bad sense of the term, but a British Constitutionalist. The land of every country belongs to the people of that country as a whole. The Crown is lord paramount of the soil, and, as such, the vicegerent of God the owner. Individual owners are mere occupiers. The position of British landlords is one of usurpation and appropriation of what does not belong to them, by exercising a taxing power, in their own right, which ought to appertain to the State alone.

Bellamy, Charles Joseph. 1884. The Way Out, Suggestions for Social Reform. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[143] We conclude, then, that the property of every person on his decease reverts to the State, a rule founded on expediency as I have suggested, on law properly construed as I have tried to explain, and on justice because what belongs to no person in particular belongs to all in general, that is to the State.

Miller, William Galbraith. 1884. Lectures on the Philosophy of Law. Charles Griffin and Co.: London.

[128-129] The fact that law defines, and, in one sense, creates the notion of property, explains and justifies the law as to the compulsory purchase of lands by public companies. … On the side of the private individual free will is thus substituted for caprice. But, on the side of the state, we observe that his right rests on recognition by it. If the state withdrew its recognition he could not himself maintain de facto possession for an hour. … And so, if he sets himself to abuse this protection, and to place himself in antagonism to the just requirements of the other members of the community, the law justly and properly withdraws its recognition in this particular form, and at the same time deprives the owner of nothing which is truly property, as it awards him compensation.

Graham, William. 1886. The Social Problem in Its Economical, Moral, and Political Aspects. Kegan Paul, Trench, and Co.: London

[348] Together with the theory of property the closely connected theory of contract will require revision. The conditions or terms under which things become mine, as well as the extent of my control over these things once acquired, will require careful scrutiny, and a severer definition. … Under the theory of absolute private property, unfettered freedom of contract, and individualism…modern society cannot live, and a social catastrophe would long since inevitably have come in this country, as it came in France, were it not that for the past fifty years we have in fact been slowly but steadily departing from the theories.

[349-350] The dilemma and antinomy then, that we are driven by forces within and without to private property as a necessary institution while yet private property is the parent, together with much good, of nearly all the evils that the mass of mankind suffers, is only to be solved or evaded by narrowing our conception of private property, retaining the institution in its essential parts—the parts which have produced good—while rejecting its adjuncts which experience and reason together show to be hurtful to the general weal. We must strive to correct some of the worst consequences that flow from it in conjunction with freedom of contracts, the contracts being often not free but extorted, and therefore unfair, sometimes really free but socially hurtful. And of these consequences the gross inequality of wealth, which carries with it, as before shown, so many evils, moral and social, is amongst the worst, and one that most requires to be lessened.

The conception of property as something that is absolutely mine, to do as I please with, must be given up, and must be replaced by the moral notion that it is in large part a trust, to be administered by me for the public good as well as for my own. Further, the amount of my compulsory contribution for worthy public purposes, particularly such as aim at raising the material condition of the poor, will have to be increased.

Lacy, George. 1888. Liberty and Law. Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co.: London.

[252] Communism and Individualism are thus, in respect of the majority, on common ground on this point, while Socialism is radically opposed to both. ‘Communism must’ says a recent writer, ‘plead guilty to the charges, first, that it means to abolish the institution of property, and, next, that it must result in crushing out all individuality. Socialism not only will do neither of these things, but the very reverse. Instead of taking property away from everybody, it will enable everybody to acquire property. It will truly sanctify the institution of individual ownership by placing property in an unimpeachable basis, that of being the result of one's individual exertions. Hereby it will afford the very mightiest stimulus for individuality to unfold itself. Property will belong to its possessor by the strongest of all titles, to be enjoyed as he thinks proper, but not to be used as an instrument of fleecing his fellow citizens.’

Arnold, Arthur. 1888. “Socialism and the Unemployed,” The Contemporary Review 53(4): 560-571.

[566] Because the right to existence involves an interest on the part of every member of the community in the soil, because the law does not and cannot sever that interest from any single acre, and allows to no man an absolute and exclusive property in land, therefore it is one of the prime duties of the State to promote whatever use of the soil is for the greatest advantage. That the present distribution of land is injurious and even dangerous, probably no one will deny.

[568-569] I uphold private property and payment of wages in relation to the work done, not so much for the advantage of proprietors and receivers as for that of the community. Ideas should be encouraged; progress is stimulated by ideas of perfection, of temperance, of unselfishness, and of charity. But in practice, my idea of society is based upon a firm guarantee of the fruits of labour and of abstinence or self-control. These fruits must be subject to public claims for the needs of society. … Private property in land is not established upon a firm, justifiable, or economic basis in this country. … We seek to cleanse, to repair, to strengthen private property by restraining excesses which Parliaments of great proprietors have sanctioned. We seek to establish private property upon justice and upon economic laws. When private property has been duly regulated, it will have an assurance it has never before possessed, and society will be relieved from the greatest danger and the most potent cause of distress.

Shaw, G. Bernard. 1889. “The Economic Basis of Socialism” Fabian Essays in Socialism edited by G. Bernard Shaw. The Fabian Society: London.

[23] This, then, is the economic analysis which convicts Private Property of being unjust even from the beginning, and utterly impossible as a final solution of even the individualist aspect of the problem of adjusting the share of the worker in the distribution of wealth to the labor incurred by him in its production.

[26] On Socialism the analysis of the economic action of Individualism bears as a discovery, in the private appropriation of land, of the source of those unjust privileges against which Socialism is aimed. It is practically a demonstration that public property in land is the basic economic condition of Socialism. But this does not involve at present a literal restoration of the land to the people. The land is at present in the hands of the people: its proprietors are for the most part absentees. The modern form of private property is simply a legal claim to take a share of the produce of the national industry year by year without working for it. It refers to no special part or form of that produce; and in process of consumption its revenue cannot be distinguished from earnings, so that the majority of persons, accustomed to call the commodities which form the income of the proprietor his private property, and seeing no difference between them and the commodities which form the income of a worker, extend the term private property to the worker's subsistence also, and can only conceive an attack on private property as an attempt to empower everybody to rob everybody else all round. But the income of a private proprietor can be distinguished by the fact that he obtains it unconditionally and gratuitously by private right against the public weal, which is incompatible with the existence of consumers who do not produce. Socialism involves discontinuance of the payment of these incomes, and addition of the wealth so saved to incomes derived from labor.

Wallas, Graham. 1889. “Property Under Socialism” in Fabian Essays in Socialism edited by G. Bernard Shaw. The Fabian Society: London.

[134] It is true that the ground on which houses are built could immediately become the property of the community; and when one remembers how most people in England are now lodged, it is obvious that they would gladly inhabit comfortable houses built and owned by the State. But they certainly would at present insist on having their own crockery and chairs, books and pictures, and on receiving a certain proportion of the value they produce in the form of a yearly or weekly income to be spent or saved as they pleased.

[135] There would remain therefore to be owned by the community the land in the widest sense of the word, and the materials of those forms of production, distribution, and consumption, which can conveniently be carried on by associations larger than the family group. Here the main problem is to fix in each case the area of ownership. In the case of the principal means of communication and of some forms of industry, it has been proved that the larger the area controlled the greater is the efficiency of management; so that the postal and railway systems, and probably the materials of some of the larger industries, would be owned by the English nation until that distant date when they might pass to the United States of the British Empire or the Federal Republic of Europe.

Hobson, John Atkinson. 1891. Problems of Poverty. Methuen and Co.: London.

[199] When it is said that ‘we are all socialists to-day’, what is meant is, that we are all engaged in the active promotion or approval of legislation which can only be explained as a gradual unconscious recognition of the existence of a social property in capital which it is held politic to secure for the public use.

Bax, Ernest Belfort. 1891. Outlooks from the New Standpoint. Swan Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[81] It is sometimes said liberty is inseparable from property, and I agree. But the individualism of private property has to-day landed us in a state of things in which the majority have no certain property at all, and therefore on the individualist's own showing the majority are deprived of liberty. Liberty, in any society, is inseparable from property. Good, but this does not say it is inseparable from private property. It does not say that it is not in antagonism to private property as we contend it is…. No! liberty may be inseparable from property, but nowadays it is assuredly inseparable from the common holding of property by the community.

Sorley, W. R. 1891. “The Morality of Nations,” International Journal of Ethics 1(4): 427-446.

[436] The state stands to its citizens in a relation which no one individual bears to another. To further its end it may take their property and even their life. It neither steals nor murders in doing so.

[440] Within a nation the state is above all individuals; and, although no citizen has a right to take or use the property of another without his consent, the state recognizes this absolute right of an individual to his property only as against other individual, not as against itself. The state, therefore, is there as a superior power to prevent, if it see fit, the individual from grossly misusing his property, or from leaving it entirely unsued, and thus depriving the nation of its share in the value which would be derived form its employment.

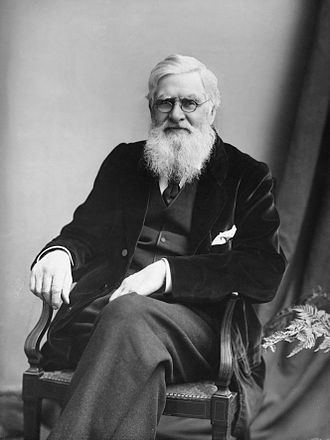

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 – 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, and biologist. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural selection; his paper on the subject was jointly published with some of Charles Darwin's writings in 1858. This prompted Darwin to publish his own ideas in On the Origin of Species.

Wallace, Alfred Russel. 1892. Land Nationalisation. Swan Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[179] The fact that the only way found by Parliament to save a nation from chronic insurrection and a people from chronic misery and starvation is thus to interfere in the case of land, proves of itself that land should not be private property, but should be held by the State for the free use and general benefit of the community. The question of how the land became the property of its present owners is not important.

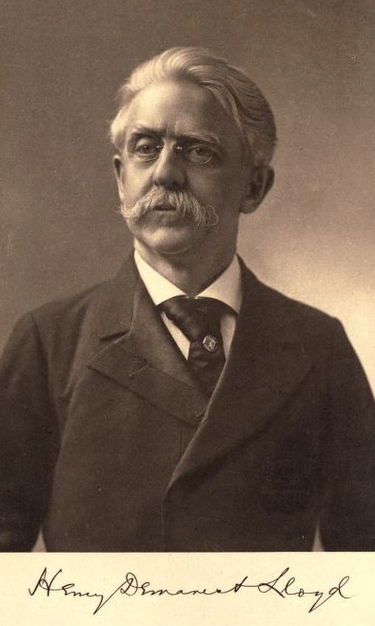

Lloyd, Henry D. 1893. “On Trusts,” The New Nation 3(24): 300-304.

[302-304] We have been fighting fire on the well-worn lines of old-fashioned politics and political economy, regulating corporations, and leaving competition to regulate itself. But the flames of a new economic evolution run around us, and we turn to find that competition has killed competition, that corporations are grown greater than the state, and have bred individuals greater than themselves, and that the naked issue of time is with private property becoming master instead of servant. Private property in many necessaries of life has become monopoly of the necessaries of life. … Private ownership when it reaches monopoly of any necessary of life must be state ruled or state owned. By tariff reform, tax reform, land tax reform, by the enforcement of reasonable prices, through the courts, by legislative authority, reviving the price regulation of the middle ages, or, these failing, by the exercise of the sovereign power of eminent domain the right of the people to a voice in the disposal of the products of their labor, and to say what they will give and what they will take, must be restored to them. ‘Any private control of a thing designed by the God of all for all,’ says the report to Congress in 1888, ‘should be regulated by all through the government.’

Commons, John Rogers. 1893. The Distribution of Wealth. Macmillan and Co.: London.

[92] To the popular apprehension, this rigid definition of property seems somewhat arbitrary. At least, from the standpoint of the economist, it is better to recognise all of the elements of legal control over valuable objects as property rights; but to designate certain of these rights as definite, and the residuum as indefinite.

Property is, therefore, not a single absolute right, but a bundle of rights. The different rights which compose it may be distributed among individuals and society—some are public and some private, some definite, and there is one that is indefinite. The terms which will best indicate this distinction are partial and full rights of property. Partial rights are definite. Full rights are the indefinite residuum. … The first definite right to be deducted from the total right of property is the public right of eminent domain. This is the definite right which belongs to the state in its organised capacity of purchasing any property whatsoever at its market value, whenever public safety, interest, or expediency requires. It is merely a definite restriction upon the unlimited control which belongs to the individual.

Wood, Joseph. 1893. “Wealth and Commonwealth,” The New Nation 3(6): 85-87.

[85] In the propaganda of socialism nothing seems to me more important than to get people to see and acknowledge the indebtedness of the individual to the community; that there would be no wealth but for the commonwealth; that the main element in property is not personal but social. It is only in fellowship and combination that property is acquired. The social life is the only answer, in fact, which meets the individual’s desire to live. It may seem for a moment that the world of labor is just a world of toiling units, each bearing the burden of its own life. But his is only a fragment of the truth. Never in any past which history brings within view has the individual ever labored to support his own life by himself alone. As soon as industrial and economic life begin to have any history at all, we are following forms of combination between man and man which daily become more intricate and complex. No progress, no wealth, no accumulated stores, no life, in fact, is possible except in fellowship. The duty to live is the duty to labor, and this becomes the duty to live in mutual helpfulness with others. … To-day we are fed in body, soul and spirit by the millions of human beings all over the wide world. … Others are always working for us. We are always being ministered unto. Day by day, hour by hour our indebtedness to the community increases. To the community we owe everything. … We talk about our right to our own! What is our own? We are bankrupts every one except by the grace of the community, and our one right is the right to serve. Each for all can be our only motto, and private property becomes a mere convention, more or less convenient, but a convention only, which society allows and which society can abolish without wronging any man.

Quelch, Harry and W. Simpson.1893. State Socialism: Is It Just and Reasonable? Report of a Debate between H. Quelch and Mr. W. Simpson at the Corporation Hall, Burnley. Twentieth Century Press: London.

[3] [Quelch:] This democratic State, then, should control all the material necessaries of human existence. Land should be common national property, and not private property at all. Land was the gift of nature or of God, whichever term they liked to use, and no man had a right to lay claim to it, for no man made it. Here they had a natural gift, and it should be enjoyed by all, just as the air we breathe. Even if the absolute power which the ownership of land gave to the landlord were always used wisely and well it would not be just.

[6] [Simpson:] Socialism proposed that land and capital should be national or State property in order that they might be used for the benefit of all. [Mr. Quelch] maintained that this was just, because it meant the placing under control of the people all the land and raw material without which human existence was impossible, and it was reasonable because it was just and was practicable.

Hoffman, Frank Sargent 1894. The Sphere of the State. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[56] The natural right to property, therefore, is ultimately resolvable into a State right. The people, as an organic brotherhood, are to decide what disposition is to be made of all property. While the good of the individual and the preservation of his right to the products of his labors are of great importance, the welfare of the brotherhood as a whole is of far more importance and should be the point of view from which the laws controlling the possession and use of property are finally determined. … The laws of property that the State enacts will seldom need to set aside the natural right to property, but will almost always confirm and strengthen that right.

[57] The supreme ownership of all the natural sources of property is with the State. The land, the water, and the air, and all that they contain are the common possession of the race. They are under the supreme control of the whole people in their organic capacity as a State. … That the community, and not the individuals of the community, originally owned the land is one of the best attested facts of history.

[58] The State has the ultimate control of and responsibility for the methods of acquiring property. If the sources of property are under the supreme control of the State, it is easy to see that all property derived from those sources should be under its control also. No individual can take any of the materials of wealth without the consent of the State, and by his labor make them his property, and the State can never rightly give this consent except with the limitation that the ultimate ownership and control of all property is with itself. While the State, therefore, fully recognizes the natural right to property that comes from labor, it cannot regard this right as absolute, but must itself determine in what way and by what means property is to be acquired.

[59] The State is also the supreme authority for determining how property should be used after it is acquired. No individual member of the State has a right to use his property as he pleases. If he pleases to use it for the injury of the State, to degrade and demoralize his fellows, the State through its government should put a limit upon his use of his property and, if necessary, deprive him of it altogether. … The principle of confiscation is a clear recognition of this right. All nations agree that if a citizen uses his property to abet the enemy in time of war, he has violated the first principles of government, and has by this act cut himself off from his normal relation to the community, and deprived himself of the advantage that before belonged to him as a member of that community. The original condition on which the State allowed him the control of his property has disappeared, and his individual right to the use of it has disappeared also.

Ely, Richard T. 1894. Socialism. Thomas Y. Crowell and Co.: New York.

[306] Private property is an exclusive right, but never an absolute right. Private property is a growth, changing both with respect to the number of things to which it extends, and with respect to the privileges which it carries with it. Legal codes will be searched in vain for an unlimited right of private property. … These limitations, when carefully examined, all mean one thing; namely, that private property has a social side. But this is not all. An examination of the nature and growth of private property and of its treatment by civilized nations, shows that in case of conflict between the social side and the individual side, the social side is dominant and the individual claims must be yielded. Private property is maintained for social purposes.

[309] The social side of private property may be further developed through public agencies. One of the principal needs is a full and complete recognition of the fact that private property exists for social purposes; for when this is generally understood, it will show itself in a multitude of legislative details, as well as in judicial decisions.

This social theory of private property justifies a regulation of its use; but it must be always borne in mind that if this regulation is carried far, the advantages of private property begin to disappear. When it becomes necessary to regulate private property minutely, we have a clear indication that private property should be replaced by public property.

Ford, Corydon Lovine. 1897. The Organic State. C. Ford: New York.

[6] Property, or material action, tends to be interpreted in the functional or universal sense, as wider economic bearing (public), instead of as holdings (private) apart from universal or functional demand in the State; it tends to interpretation as use in full division of labor (public), instead of withholdings (private) from full demand upon it as division of labor; value in a thing is its office as division of labor.

[9-10] Let such recast the notion of a man’s house, held as private property. The value of the house is not possession but employment or control of it by this man in his action, necessarily public—action necessarily public because a man cannot act outside of the State. He built the house with the notion of equalizing conditions in life, of which a bare shelter is the narrowest view. He built the house and uses it that he may be an efficient member of democracy—that he may be a man. He built the house under the exactions of the State, as impelled and conditioned by it. … He extended life in a sum which is the house and its implications; in such part he built the State; so far as the uses of the house go he created the State. And this is the value of the house, namely, a piece of action jointly in a community of men. Furthermore, we know that the man did not build the house alone; the State fed and clothed him while he worked; other labor supplied him tools and material. The thing was impossible outside of a connected life. He is a factor in a whole of action which resulted in building the house, just as in another direction it resulted in making a legal decision. We know by this that the State itself built the house, using the man as one among a thousand contributory items in it just as it used the judge in the legal decision. And as the latter is public, or disposable by the public, so is the house.

Ely, Richard Theodore. 1899. “Political Economy,” in Political Economy, Political Science and Sociology, edited by Richard T. Ely. The University Association: Chicago.

[543-544] The first fundamental institution in the distribution of wealth is Property. … For we must think of private property not as a single right but as a bundle of rights.

Hobson, John Atkinson. 1900. “The Ethics of Industrialism” in Ethical Democracy edited by Stanton Coit. Grant Richards: London.

[103-104] In what bodies public ownership and control of the land should be vested, how such ownership should be acquired, how such control enforced, are matters of politics, but that private ownership of any lands is inconsistent with the principles of democracy in a thickly peopled State should be self-evident. … A fuller recognition of the meaning of the corporate life of a society will oblige us to admit that this growing industrial life of the State is a necessary condition of its moral health. Just as it is essential to the progress of the moral life of the individual that he shall have some ‘property,’ some material embodiment of his individual activity which he may use for the realisation of his rational ends in life, so the moral life of the community requires public property and public industry for its self-realisation, and the fuller the life the larger the sphere of these external activities.

Dight, C. F. 1905.“Socialism and the Farmers,” The International Socialist Review 5(10): 604-609.

[607] The government, though it perhaps intended to protect and help all, has actually thwarted its own ends by giving perpetual private ownership to land. Socialists would again make land public property to serve the needs of all. The people in doing this would probably favor the gradual relinquishment of private ownership of land, as it was favored by Lincoln to gradually liberate the slaves, and of the unused land held for speculation first, letting it as rapidly as relinquished revert to the government, thus making it again the property of the whole people, as our lakes and rivers are, and to be used for the most part co-operatively. … The great Socialistic principle to hold to is this: That the whole people should own the productive property of the nation, and the resources on which all depend for life and comfort and give each worker access to them to earn a living by any honest labor of hand or brain, and to each worker the full product or equivalent of his toil. Land, then, as it gradually becomes owned by the government, will be brought under use by giving to all who want land for actual productive purposes, the right, not to perpetually possess, but the right to use land co-operatively, or possibly privately, so long as they use it for the best interest of themselves and the public.

MacDonald, James Ramsay. 1905. Socialism and Society. Independent Labour Party: London.

[180-181] The Socialist creed upon property is perfectly simple. It considers that property can be legitimately held only as the reward for services. It condemns the existing state of things, because those who do no service own most property. Socialism is, therefore, a defence of property against the existing order. … Its business is not to prevent accumulation, or prohibit its transference, but to provide that such accumulation is not made at the public expense, and not employed to keep the public in subjection for all generations. But, on the other hand, the Socialist contends that the community, as well as the individual, creates values which it should hold as property and devote to common interests. Every valid argument which establishes the right of individuals to own and use property, is equally applicable to a defence of the community's right to own and use property. Social income, in the shape of taxes and rates, is not private income appropriated, and the theory and method of taxation should be revised, so that values created by the public may find their way into the public exchequer. This would lead to a substantial redistribution of wealth, because whilst tending to deprive parasitic classes of their nourishment, it would ease industrious classes of burdens and provide nourishment for the active functions of the community.

Hobson, John Atkinson. [1909] 1974. The Crisis of Liberalism. Harper & Row Publishers: New York.

[vii] For then for the first time Liberalism was urged to apply the principles of self-government in such a manner as involved reformation in the ownership of property. The failure to carry through this policy in the mid-‘eighties was a humiliation which bred self-distrust.

Richardson, Noble Asa. 1910. Industrial Problems. Charles H. Kerr and Company: Chicago.

[180] Then private property is by no means destroyed by Socialism. The fact is, so far as the great mass of humanity is concerned, Socialism would tremendously augment private property. The cry of the capitalists about Socialism's destroying private property has its basis in the fact that the property created would belong to the creator and not to the exploiters—it would destroy their private property in labor-power. But certainly labor would find nothing to regret in that condition of things. There is here involved no question of the creation of private property; the matter that worries the capitalists is the manner of its proposed distribution. The would-be millionaire could not get it; therefore, he argues, it would not exist. Socialism demands the collective ownership of the things that are now used as a means through which to exploit labor; or, to be more exact, the things used collectively—the sources of our subsistence and all sorts of public institutions.

Jones, Henry. 1909-1910. “The Ethical Demand of the Present Situation,” Hibbert Journal 8. Quoted in T.H. Green and the Development of Ethical Socialism by Matt Carter (Imprint Academic, 2003).

[537] So far from destroying the rights of property, [socialism] is defending them by defending them a little more justly, which is their surest defence of all.

Hobhouse, Leonard T. 1910. “Contending Forces,” English Review VI: 359-71.

[359] …we are, in fact, witnessing in regard to the land one of those slow changes of mental attitude which are more potent than any mere revolution. From looking upon it as the property of a small number of individuals who were once politically and still remained socially leaders of the nation, people have come to look on it rather as the greatest national asset, of which the owner is a steward who may be called to account, which must be used for national purposes … In this sense, the Progressive ‘trend’ is setting strongly towards making England the property of the English nation, not by any wholesale expropriation of individuals, still less by any high-handed disregard of prescriptive right, but rather by the moderate and cautious but resolute and many-sided application of the principle of public overlordship.

MacDonald, James Ramsay. 1911. The Socialist Movement. Henry Holt: New York.

[132] This is particularly true of private property in natural monopolies, like land. The experience of every people in the world, whether it be a barbaric tribe or a civilised nation, is that, when land becomes subject to private proprietorship, poverty inevitably follows.

In consequence of this the Socialist has come to the conclusion that where industrial capital is not the subject of communal control and use, and where natural monopolies are in the possession of individuals, it is economically impossible for masses of people to acquire private property at all. The socialisation of certain forms of property is a condition necessary for the general diffusion of private property. The nationalisation of industrial capital and of the land is therefore not the first stage of the abolition of all private property, but is exactly the opposite. The result of the operations of a society which allows private property in everything, is determinedly a law of concentration and accumulation, the effect of which may be expressed in biblical language: ‘Unto every one that hath shall be given, but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.’ The idea that capitalist society is based on private property is a mere chimera.

Haywood, William Dudley and Frank Bohn. 1911. Industrial Socialism. Charles H. Kerr and Co.: Chicago.

[4] Socialism is the future system of industrial society. Toward it America, Europe, Australasia, South Africa and Japan are rapidly moving. Under capitalism today the machines and other means of wealth production are privately owned. Under Socialism tomorrow they will be collectively owned. Under capitalism all popular constitutional government is merely political. Its main purpose is the protection of private property. Industry is at present governed by a few tyrants. Its purpose is to take from the workers as much wealth as possible. Under Socialism industrial government as well as political government will be democratic. Its purpose will be to manage production and to establish and conduct the great social institutions required by civilized humanity. Political government will then, of course, have ceased to exist.

Croly, Herbert David. 1911. The Promise of American Life. The Macmillan Co.: New York.

[209] A democracy dedicated to individual and social betterment is necessarily individualist as well as socialist. It has little interest in the mere multiplication of average individuals, except in so far as such multiplication is necessary to economic and political efficiency; but it has the deepest interest in the development of a higher quality of individual self-expression. There are two indispensable economic conditions of qualitative individual self-expression. One is the preservation of the institution of private property in some form, and the other is the radical transformation of its existing nature and influence. A democracy certainly cannot fulfill its mission without the eventual assumption by the state of many functions now performed by individuals, and without becoming expressly responsible for an improved distribution of wealth.

Bax, Ernest Belfort. 1912. Problems of Men, Minds, and Morals. Small, Maynard, and Co.: Boston.

[118-119] The modern Socialist recognises that only through the economic change he postulates, from individual to collective ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange, can Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity be realised. The old attempts to realise them have conspicuously failed. The liberty aimed at by Socialism is freedom of development for the individual as for Society. This liberty the Socialist sees to be impossible under a regime of private property-holding in the means of production. All the existing trammels on freedom, alike for the individual and for Society, the Socialist finds traceable, in the last resort, to the system of private ownership in these means of production.

The institution of private property, which, in earlier stages of Society, played its part as a guarantee of freedom and progress, has, in these latter days, become a stumbling block and a hindrance—in a word, the enemy of progress.

[149] Socio-economic Liberty, the right of the community to freedom of action as to its economic conditions, is obstructed at every turn in our existing social organisation by the property interests of individuals and classes. This is abundantly clear whenever any attempt at Socialistic legislation, however mild in character, is made within the framework of the existing State. It is then seen that every proposal through which the bulk of the community should be enabled to come by its own, in however slight a measure, encounters an impregnable stone wall of class interests. Hence the economic subjection of the proletariat and hence the impossibility of socio-economic Liberty so long as the capitalistic State exists, which means, so long as the land and the means of production remain private property.

Vinogradoff, Paul. 1914. Common-Sense in Law. Henry Holt: New York.

[63] While this first group of rights clusters round the idea of personality, a second group is formed round the idea of property. … It rests with the State to determine the rules as to accumulation, disposal and protection of property.

Melvin, Floyd James. 1915. Socialism as the Sociological Ideal. Sturgis and Walton Company: New York.

[185] How much greater will be the popular support of the real rights of private property when all feel personally interested in the matter? Under socialism however we may be assured that property would receive no direct consideration. Only as it ministers to the needs of man would property possess ‘rights.’

Emerick, Charles F. 1915. “The Courts and Property,” in Readings on the Relation of Government to Property and Industry edited by Samuel Peter Orth. Ginn and Company: Boston.

[78-79] The institution of private property depends upon the general consensus of opinion which varies from age to age. It is a common error to suppose that whatever is always will be. Take the right of a man to interfere with the business of another by normal competition, by way of illustration. This is regarded as a matter of course today, but there was a time when the right to engage in a given trade was restricted to the members of a certain guild, and a man was not at liberty to enter any pursuit he might elect. … Likewise, property rights are no more absolute than is the right of competition. Slave property, once nationwide, became sectional and then disappeared altogether. Property in general depends as much upon considerations of social utility as property in slaves. … The ownership of land was vested in the community and not in private hands until comparatively recent times. The powers and franchises granted corporations are wholly optional with the several states, and depend upon considerations of social expediency. But for the social will embodied in positive law, there would be no such thing as theft.

At the present time property rights are being modified in various directions. There is a strong tendency to municipalize or nationalize certain industries. … The social obligations resting upon private property are increasing. The abridgment of property rights is reflected in the lighter punishments provided for offenses against property. … As humanitarian considerations have gained ground, private property has lost something of the sanctity in which it was once held. It is remarkable how quickly even the staunchest defenders of property sometimes face about and demand an abridgment of property rights. All that is needed is some event that brings out clearly the opposition between private and public interests.

Bruce, Andrew Alexander. 1916. Property and Society. A. C. McClurg and Co.: Chicago.

[3] Involving as it does the right to contract and to acquire, and since in the last analysis all contracts are dependent upon the sanction of an organized society, the private property right is a right which is social rather than natural. Organized society involves a public peace and a more or less extended reign of law, and, when once the right to take and to hold by force is denied, the protection which is afforded by the state or the community is the only guarantee of property even in that which is tangible and physical. A right, indeed, which society refuses to recognize and protect can have but little value.

[4] It has been the fear, indeed, of the financially strong but of the numerically weak that without law and order there would be no security to private property that has been at the foundation of our law and our courts, our police system, the lighting of our streets and cities, and, to a large extent, of our standing armies. We have, however, yet to find any written definition of the terms ‘property’ and ‘liberty,’ except perhaps that of the leader of the Shay Rebellion, which does not presuppose the duty of a social use and the right of an ultimate public control, and the uniformity of these definitions and conceptions can only be due to the fact of the realization and belief in the necessity of public protection, and as an incident thereto of governmental regulation.

[5] In none of these countries [England, America, Prussia] does the right of property involve the right to misuse nor the right to use it to a social disadvantage, and, in all of them the ultimate control of the public is presupposed.

Mecklin, John Moffatt. 1920. An Introduction to Social Ethics: The Social Conscience in a Democracy. Harcourt, Brace and Howe: New York.

[302] Society assures to each of its members in the right of private property the power to secure and exercise the means necessary for the expansion of personality and the development of capacity as moral creatures. The general will that provides the sanction for the right must also determine the scope and purpose of the right. It must be exercised in the interest of the social good.

[303] The institution of private property must be emancipated from the moribund legal abstractions of the eighteenth century. It must cease to be a dead juridical entity and serve the needs of a progressive society, and that without surrendering its economic or ethical value. … These are only of value in so far as they enjoy the moral sanction of the community.

[303] The real safeguard of private property, therefore, is… in a sane and intelligent adaptation of the institution to the needs of the community.

[312] The state gives to the owner of property power over the lives and activities of his fellows, not in order that they may be selfishly and injuriously exploited but on the supposition that in the long run this is the best way in which to develop natural resources, create economic goods, provide employment for men and further the welfare of society. That is, this power over others by virtue of the possession of property is a social trust and is safeguarded only on the supposition that it is exercised as such.

Carver, Thomas Nixon. 1921. Principles of National Economy. Ginn and Carver: Boston.

[113] So important has this become that we are in the habit of speaking of property almost as though it consisted exclusively in this protection afforded by the state. Thus the individual may possess an object, but he is not said to have property in it unless the state recognizes his right to possess it and warns others not to meddle with it, undertaking to punish anyone who does. Moreover, the individual’s property rights in a thing extend only so far as the state recognizes and warns others not to meddle. In some cases, for example, an owner of land is not permitted to exclude other persons from walking across it, in which cases those other persons are said to have right of way. There are numerous other limitations upon the property rights.

Gilchrist, Robert Niven. 1921. Principles of Political Science. Longmans, Green and Co.: London.

[169] Property, like liberty, contains no absolute right in itself. At any time the claims of the state may be so paramount, e.g., in a great war—that the usual property rights may be temporarily suspended. So it is also with confiscation of property. Property may be confiscated either as a punishment or for reasons of state. The whole question of taxation is also connected with property. It depends on the particular views prevailing in a community at any period whether any given type of property shall be taxed, or taxed more heavily than any either type. Thus speculation in buying and selling land near rising towns may be checked by a tax on unearned increment, or increase in values caused not by the investor's exertions but by the growth of the community. ‘Vested’ interests, again, are often said to confer certain property rights on individuals. Vested interests arise from length of tenure, and it is held that the individual has a ‘right’ to expect the continuance of the conditions under which he bought or developed his property. Such an idea rests on a wrong idea of the state. The state cannot allow any interests to continue if these interests defeat the object of the state’s existence. No government can bind its successors for ever to a certain line of action. The change of circumstances in time may completely alter the meaning of a certain type of property or investment. The common welfare, not individual interests, is the main concern of the state.

Hobhouse, Leonard T. 1922. Elements of Social Justice. George Allen and Unwin: London.

[31] The inheritor of wealth talks of ‘my’ property, and resents interference with it by society, forgetting that without the organized force of the community and the rule of law, he could neither inherit nor be secure from moment to moment in his possession.

[159] For the present we must be content to affirm that property, so far as it implies the ultimate control of the industrial mechanism, is a communal function, whereas the right of the individual is that of effective participation in common decision and of the most direct participation in those which most nearly concern him.

[161] The State organization is to begin the basis of security, and therewith (among other things) of property itself. That considering alone gives to the community the last word in deciding what rights of property it will recognize, and on what terms.

[163] Since property confers exclusive rights there must, to justify individual ownership, be some reason for giving to some definite individual rights as against others. If there is no special reason the basis of exclusive ownership fails, and all have an equal right to participate, i.e. the only rational claim is that of the community.

Willoughby, Westel Woodbury. 1924. The Fundamental Concepts of Public Law. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[444] Of the complete jurisdiction of a sovereign State over a property within its territorial limits, whether for purposes of taxation, of eminent domain, or the regulation of its use in private hands, there is no dispute.

Wilde, Norman. 1924. The Ethical Basis of the State. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

[119] Property can be held only as its owner pays his taxes and refrains from using it in a way detrimental to the public interests. Life itself has no absolute privilege but is respected only as it conforms to the necessities of the social welfare. My rights belong, not to myself in my private capacity, but to the part I have to play in the human drama, and if I fail to play it well I can make no valid claim to the forbearance of my fellows.

MacDonald, James Ramsay. 1924. Socialism: Critical and Constructive. The Bobbs-Merrill Company: Indianapolis.

[142] Here the Socialist can lay down one of the foundation stones of his reconstructed society. The personal enjoyment of property possible to the masses of people is from collective and not from individual ownership. … [Communal property] belong to a better class of motive than the purely personal one, and we may hope that in time that class will predominant, but that is not yet.

Hughan, Jessie Wallace. 1928. What is Socialism? Vanguard Press: New York.

[70] Socialists heartily accept the general argument of Henry George that the land, with all it contains, is the rightful property of the community, and that no man should be permitted to appropriate the unearned increment in land values contributed by society.

Laski, Harold Joseph. 1930. The Grammar of Politics. Yale University Press: New Haven.

[87-88] …[A]ll systems of property are justified only to the degree that they secure, in their working, the minimum needs of each citizen as a citizen. No legal rights, therefore, are ethically valid which do not arise from a contribution made to that need. … My property is, from the standpoint of political justice, the measure of economic worth placed by the State upon my personal effort towards the realization of its end. Obviously, therefore, there can be no property-rights without functions.

Lippmann, Walter. 1934. The Method of Freedom. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[100-101] It has been in fashion to speak of the conflict between human rights and property rights, and from this it has come to be widely believed that the cause of private property is tainted with evil and should not be espoused by rational and civilized men. In so far as these ideas refer to plutocratic property, to great impersonal corporate property, they make sense. These are not in reality private properties. They are public properties privately controlled and they have either to be reduced to genuinely private properties or to be publicly controlled.

Coughlin, Charles E. 1934. Eight Lectures on labor, Capital, and Justice. The Radio League of the Little Flower: MI.

[116] I feel that you will heed me when I tell you of your rights to property and of your duties to your fellowmen—rights and duties that lead us to economic liberty. We maintain that ultimately and primarily all property belongs to the creator. Under the title of stewardship the right to own private property has been given to man by Divine Providence so that both individuals and the human race may survive. No man and no group of men may exclude others from ownership.

Coughlin, Charles E. 1935. Lectures on Social Justice. The Radio League of the Little Flower: Michigan.

[17-18] …[T]hese shall be the principles of social justice towards whose realization we must strive:

1. I believe in liberty of conscience and liberty of education, not permitting the state to dictate either my worship to my God or my chosen avocation in life.

2. I believe that every citizen willing to work and capable of working shall receive a just, living annual wage which will enable him to maintain and educate his family according to the standards of American decency.

…

5. I believe in upholding the right of private property but in controlling it for the public good.

…

16. I believe in preferring the sanctity of human rights to the sanctity of property rights….

[26] Although there are two kinds of property rights, namely, private property owned by private individuals and public property owned by the nation, the ownership of private property does not argue that the owner of it may do with his property what he pleases. If I own a shotgun that is no argument why I may kill my neighbor’s child. If I own a factory that is no argument why I may starve the laborers to make profits and profits only for stockholders. All property is subject to control. All Property is owned primarily by Almighty God Who gave us this earth and the factories—to be used, if not owned, for the common welfare of every person.

Louis C. Fraina (1892–1953) was a founding member of the American Communist Party in 1919. After running afoul of the Communist International in 1921 over the alleged misappropriation of funds, Fraina left the organized radical movement, emerging in 1926 as a left wing public intellectual by the name of Lewis Corey.

Corey, Lewis. 1935. “The Clash of New and Old Social Systems,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 178(Mar.): 1-8.

[7] These developments are emphasized by the increasing intervention of the state in industry. Yet the ‘rights’ of private property and private appropriation persist, while the economic forms of a new social system press for release against the limitations of the outworn capitalist social relations of production. … It threatens the destruction of civilization. These are the reactionary results of capitalism’s preventing the economic forms of the new social system from moving onward to new relations of production, to socialism.

Leighton, Joseph Alexander. 1937. Social Philosophies in Conflict. D. Appleton-Century Company: New York.

[332-333] So intimate and indissoluble is our economic interdependence to-day that the insistence on the property rights of another and simpler era is like a mad bull at a large china shop. Property is affected with a public interest, precisely in proportion to the degree in which it is tied up with our economic interdependences.

[334] If the right of property is relative and depends upon the use made of it, is there any limit beyond which organized society may not go in controlling it? May not society take all my property? Of course it can. The power of the State is absolute.

Hale, Robert L. 1939. “Our Equivocal Constitutional Guaranties Treacherous Safeguards of Liberty,” Columbia Law Review 39(4): 563-594.

[188] It is in defining what is each person’s property that the law confers unique rights on each, and imposes unique duties.

Ezekiel, Mordecai. 1939. Jobs for All. Alfred A. Knopf: New York.

[279-280] From the very beginning the people through government have imposed certain limitations on the freedoms of private capitalism. … These limitations recognized that private property, being dependent on the State for protection, must support the State and pay its due proportions of the cost of protections. … Only thus limiting the uses made of individual properties can the people of a community as a whole ensure the continued usefulness and value of all the property of the community.

Clark, John Maurice. 1939. Social Control of Business. McGraw-Hill Company: New York.

[94] Most people think of property as a tangible thing which somebody owns. But the important question is What is this thing we call ownership? Ownership consists of a large and varied bundle of rights and liberties.

[94] The economic substance of ownership consists of the benefits one can derive from one’s own property, and these depend upon the things he is free to do with it. And these in turn are bounded by the law, which lays down the things one may or not do; hence the law determines the real content of property.

Leacock, Stephen. 1942. Our Heritage of Liberty. Dodd, Mead and Company: New York.

[72-73] There was, unseen, the question of the right of property and especially property in land. … Similarly, the inheritance and the bequest of property seemed as natural as death itself. He who went away gave his goods to those he left behind. To many pious and well-to-do people such ideas about ownership and property and the sanctity of the owners dying wish, seemed part of the structure of social life, beyond man’s right to alter. This notion of the sanctity of property clung especially to property in land. … There came a day when all the free land was gone. The landless man had lost his natural right to the soil. … We now see that ownership of land must be limited by certain responsibility about its use. The owner can no longer ‘do what he wants with his own.’ That depends on what he wants to do. If he wants to leave his land idle and undeveloped, then the government may expropriate it for other uses.

Shaw, Bernard. 1971. The Road to Equality: Ten Unpublished Lectures and Essays, 1884-1918. Beacon Press: Boston.

[37] There is no divine right of property. Nothing is so completely a man’s own that he may do what he likes of it.