Law › Rejoinders

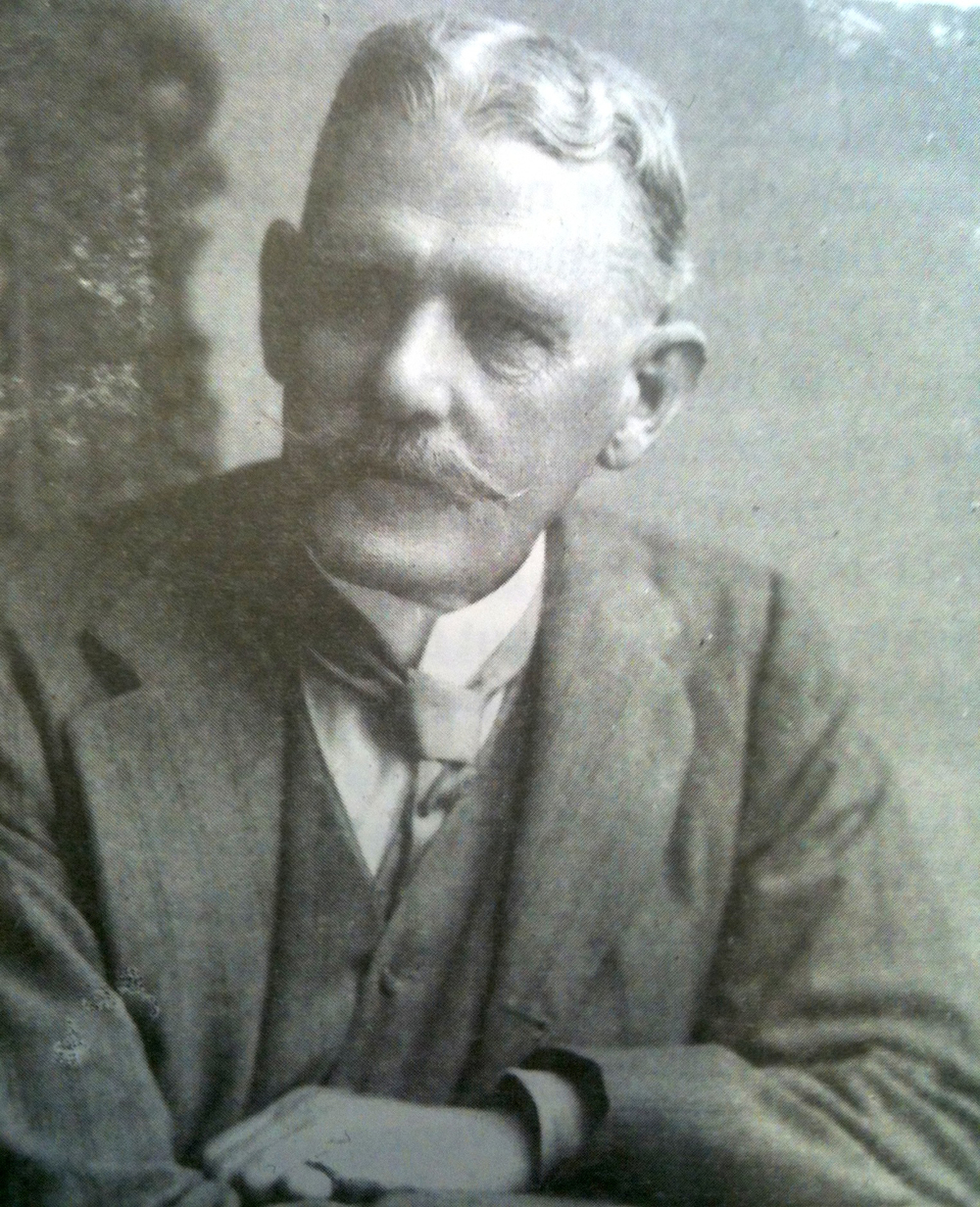

Sir Thomas Erskine Holland (1835 – 1926) was a British jurist. His prolific scholarly work, including an often-cited treatise in legal philosophy (Elements of Jurisprudence, 1880), his co-founding and editorship of Law Quarterly Review and his service as a university judge earned him the titles of a King's Counsel and a Fellow of the British Academy, as well as a knighthood in 1917.

Holland, Thomas Erskine. 1888. The Elements of Jurisprudence. Clarendon Press: Oxford.

[34-35] Natural law, or natural equity, has been often called in to justify a departure from the strict rules of positive law.

With the changing ideas of society cases of course often occurred when the law of the State was found to be in opposition to the views of equity entertained by the people or by leading minds among them. The opposition would be said in modern language to be between law and morality. But law and morality in early times were not conceived of as distinct. The contrast was therefore treated as existing between a higher and a lower kind of law, the written law which may easily be superseded, and the unwritten but immutable law which is in accordance with Nature.

And this way of talking continues to be practised to the present day. Long after the boundary between law and morality had been clearly perceived, functionaries who were in the habit of altering the law without having authority to legislate found it convenient to disguise the fact that they were appealing from law to morality, by asserting that they were merely administering the law of Nature instead of law positive.

Donisthorpe, Wordsworth. 1892. “The Limits of Liberty” in A Plea for Liberty edited by Thomas Mackay. John Murray: London.

[122] Law and liberty ought to exist side by side, the former protecting and guaranteeing the latter. When the two are divorced, law degenerates into tyranny, and liberty into license. Progress without order is impossible, and law is simply regulation, order being its essence…. The endeavour should therefore be so to regulate, that the highest and noblest instincts and aspirations of man shall have full scope for their development and exercise, in every department and condition of life. This is always difficult enough, for society is in conspiracy against non-conformity; how much more difficult then will it be when positive law is invoked to enforce and maintain uniformity in the domain of labour, and in the affairs of social life? It might be urged that the regulation of the hours of labour will not necessarily involve the abnegation of individual rights in the manner described. But we reply that, as the logical outcome of the regulation sought, it would be inevitable.

Lilly, William Samuel. 1892. On Right and Wrong, third ed. Chapman and Hall: London.

[112-113] Right is founded on necessity. What is necessary and immutable cannot proceed from the accidental and changeable. And rights are subjective expressions of Right. To me it is evident, upon the testimony of reason itself, that there are certain rights of man which exist anterior to and independently of positive law, which do not arise ex contractu or quasi ex contractu, and which may properly be called natural, because they originate in the nature of things. And here let me express my regret at the scanty and uncertain treatment which this subject received from one of the most accomplished of English jurisprudents. … The law of nature, as I understand it, and as I believe the Roman jurisconsults, following the great Hellenic philosophers from Aristotle downwards, understood it, belongs to the domain of the ideal. It is the type to which positive law should endeavour, as far as may be, to approximate; but the approximation must vary indefinitely according to social conditions. I am well aware that what is noumenally true may be phenomenally false; that in the life of men, principles must be viewed not in the abstract but in the concrete, as embodied in actual facts and institutions.

[114] The law of nature is an expression of the nature of things in their ethical relations. The natural rights of man have an ideal—which means most real—value, as showing the goal to which society, in unison with individual efforts, should tend. We live in a world of objects conditioned by ideas. A right is that one possession of the individual, with which, in virtue of the moral law, no power outside him can interfere. And what is right, in another, is duty in me. All human rights are really but different aspects of that one great aboriginal right of man to belong to himself, to realise the idea of his being. And justice means respect for those rights. In strictness, positive law—the rule of reciprocal liberty—does not make but merely recognises and guarantees them. A Praetorian edict, an Act of Parliament, is not their source but their channel. Our codes are only formulas in which we endeavour, with greater or less success, to apply, in particular conditions of life and social environment, the dictates of that universal law which is absolute and eternal Righteousness.

Smith, George H. 1895. “The Theory of the State,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 34(148): 189-334.

[289] The term natural right, or natural law, is a mere translation of the jus naturale of the Roman lawyer; and, in the Latin, the term jus natura is precisely equivalent; but these terms are commonly translated by us by the expressions, ‘natural law’ and ‘the law of nature;’ and, consequently, the same ambiguity, as in the case of the law, is presented. Hence, the modern English jurists, having no other conception of law than as being merely legislation, suppose that the term law is here used in the same sense, and that to account for the existence of natural law, or the law of nature, a legislator must be supposed. But obviously, the Roman lawyers, in speaking of natural law (jus naturale), which, they defined as the law, or jus, ‘which natural reason has established among all men,’ did not use the term, law, or jus, in the sense of legislation, or conceive that a legislator was implied by it; nor, so far as I know, has any one, other than the Austinian jurists, ever done so.

On the contrary, all that is implied by the term, natural right—which is but another expression for right reason—is, that there are certain natural principles, governing the jural relations of men, determined or established by reason.

[295] Our proposition, it will be observed, asserts that natural right constitutes an integral part of the actual law of every country. Those, therefore, who regard it merely as the material out of which, or the norm after which, the law ought to be fashioned, in effect deny the proposition, and also, in effect, deny the existence of natural right, which, from its essential nature, must be regarded as asserting its own paramount obligations over government as well as over individuals. But to this class belong many of the theoretical or philosophical, as distinguished from the historical jurists, of modern Europe. These accept the doctrine of natural right without reservation, but, owing to their want of familiarity with the positive law, or to other causes, do not seem fully to have grasped its significance. The true expression of the doctrine, I repeat, is that justice, or natural right, so far as its principles are determinate, constitutes in every commonwealth, not merely an ideal to be attained by legislation, but an integral or component part of the actual or positive law of the land, as binding on the courts and the State generally, as any other part of the law, and that its violation by either is not only unjust but unlawful; and that this is to be understood not merely as a philosophical theory but as a received principle of every system of positive law. [T]he writers referred to…seem to assume that they are not in fact law, and can become law only by some sort of legislative transmutation.

Carus, Paul. 1904. The Nature of the State. Open Court Publishing Co.: Chicago.

[40-41] It is customary now to reject the idea of jus naturale as a fiction, to describe it as that which according to the pious wishes of some people ought to be law, so that it appears as a mere anticipation of our legal ideals appealing to the vague ethical notions of the people. Law, it is said, is nothing primitive or primordial, but a secondary product of our social evolution, and the intimation of jus naturale is a fairy-tale of metaphysics, which must be regarded as antiquated at the present stage of our scientific evolution. It is strange, however, that those who take this view fall back after all upon nature as the source of law; they derive it from the nature of man, from the natural conditions of society, and thus reintroduce the same old doctrine under new names—only in less pregnant expressions.

Most of these criticisms are quite appropriate, for there is no such thing as an abstract law behind the facts of nature; no codified jus naturale, the paragraphs of which we have simply to look up like a code of positive law. In the same way there are no laws of nature; but we do not for that reason discard the idea and retain the expression. If we speak of the laws of nature, we mean certain universal features in the nature of things, which can be codified in formulas. Newton's formula of gravitation is not the power that makes the stones fall; it only describes a universal quality of mass concisely and exhaustively. In the same way the idea of a jus naturale is an attempt to describe that which according to the nature of things has the faculty of becoming law.

The positive law is always created by those in power; if their formulation of the law is such as would suit their private interests alone, if for that purpose they make it illogical or unfair to other parties, it will in the long run of events subvert the social relations of that State and deprive the ruling classes of their power; in one word, being in conflict with the nature of things it will not stand.

[42] Thus we are quite justified in saying that the positive law obtains, while the natural law is that which ought to obtain; the positive law has the power, the natural law the authority; and all positive law is valid only in so far as it agrees with the natural law; when it deviates from that, it becomes an injustice and is doomed. In a word, the jus naturale is the justice of the positive law and its logic.

Korff, S. A. 1923. “The Problem of Sovereignty,” The American Political Science Review 17(3): 404-414.

[406-407] Thus there arose a new school of jurists who went to the other extreme, denying any meaning in sovereignty and endeavoring to treat it as dead or non-existent. … We can easily follow [Duguit], when he asserts that the state must be subject to the law, because the state is an instrument and not an end; we have to introduce a slight correction, however, when he further says that the rule of law ‘alone is supreme.’ Unfortunately this does not apply to every state; the rule of law ought to be supreme, but is not yet absolutely dominant everywhere. … The English language never even knew of any special term corresponding to the continental European words Droit, Rect, Pravo, and for the simple reason that the state as conceived by those peoples never was the exclusive creator and unlimited controller of the social and legal forms of life.

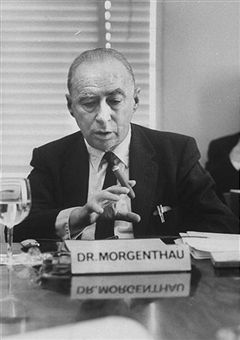

Hans Joachim Morgenthau (1904 – 1980) was one of the leading twentieth-century figures in the study of international politics. He made landmark contributions to international relations theory and the study of international law, and his Politics Among Nations, first published in 1948, went through five editions during his lifetime.

Morgenthau, Hans J. 1940. “Positivism, Functionalism, and International Law,” The American Journal of International Law 34(2): 260-284.

[267] The basic assumption of juridic positivism, that its exclusive subject-matter is the written law of the state, leads legal science not only to the inclusion of alleged legal rules which no longer have or never have had legal validity, but also to the exclusion of undoubtedly valid rules of law. Positivist jurisprudence, starting with the axiom of ‘legal self-sufficiency,’ separates the law from other normative spheres, that is, ethics and mores, on the one hand, and from the social sphere, comprehending the psycho-logical, political, and economic fields, on the other hand. … It proceeds on the assumption that the law, as it really is, can be understood without the normative and social context in which it actually stands.