Contract › Rejoinders

Maine, Henry Sumner. 1861. Ancient Law. John Murray: London.

[309] The Social Contract or Compact is the most systematic form which has ever been assumed by the error we are discussing. It is a theory which, though nursed into importance by political passions, derived all its sap from the speculations of lawyers. True it certainly is that the famous Englishmen, for whom it had first had attraction, valued it chiefly for its political serviceableness, but, as I shall presently attempt to explain, they would never have arrived at it, if politicians had not long conducted their controversies in legal phraseology. Nor were the English authors of the theory blind to that speculative amplitude which recommended it so strongly to the Frenchmen who inherited it from them. Their writings show they perceived that it could be made to account for all social, quite as well as for all political phenomena. They had observed the fact, already striking in their day, that of the positive rules obeyed by men, the greater part were created by Contract, the lesser by Imperative Law. But they were ignorant or careless of the historical relation of these two constituents of jurisprudence. It was for the purpose, therefore, of gratifying their speculative tastes by attributing all jurisprudence to a uniform source, as much as with the view of [310] eluding the doctrines which claimed a divine parentage for Imperative Law, that they devised the theory that all Law had its origin in Contract. In another stage of thought, they would have been satisfied to leave their theory in the condition of an ingenious hypothesis or a convenient verbal formula. But that age was under the dominion of legal superstitions. The State of Nature had been talked about till it had ceased to be regarded as paradoxical, and hence it seemed easy to give a fallacious reality and definiteness to the contractual origin of Law by insisting on the Social Compact as a historical fact.

Spencer, Herbert. 1883. Social Statics. D. Appleton and Co: New York.

[223] It is only by bearing in mind that a theory of some kind being needful for men they will espouse any absurdity in default of something better, that we can understand how Rousseau’s doctrine of Social Contract ever came to be so widely received. … Observe the battery of fatal objections which may be opened upon it.

In the first place, the assumption is a purely gratuitous one. Before submitting to legislative control on the strength of an agreement alleged to have been made by our forefathers, we ought surely to have some proof that such agreement was made. But no proof is given. On the contrary, the facts, so far as we can ascertain them, rather imply that under the earliest social forms, whether [224] savage, patriarchal, or feudal, obedience to authority was given unconditionally; and that when the ruler afforded protection it was because he resented the attempt to exercise over one of his subjects a power similar to his own—a conclusion quite in harmony with what we know of oaths of allegiance taken in later times.

Again; even supposing the contract to have been made, we are no forwarder, for it has been repeatedly invalidated by the violation of its terms. There is no people but what has from time to time rebelled; and there is no government but what has, in an infinity of cases, failed to give the promised protection. How, then, can this hypothetical contract be considered binding, when, if ever made, it has been broken by both parties?

But, granting the agreement, and granting that nothing positive has occurred to vitiate it, we have still to be shown on what principle that agreement, made, no one knows when, by no one knows whom, can be held to tie people now living. Dynasties have changed, and different forms of government have supplanted each other, since the alleged transaction could have taken place; whilst, between the people who are supposed to have been parties to it, and their existing descendants, unnumbered generations have lived and died. So we must assume that this covenant has over and over again survived the deaths of all parties concerned! Truly a strange power this which our forefathers wielded—to be able to fix the behaviour of their descendants for all futurity! What would any one think of being required to kiss the Pope’s toe, because his great-great-great grandfather promised that he should do so?

However there never was such a contract. If there had been, constant breaches must have destroyed it. And even if undestroyed it could not bind us, but only those who made it.

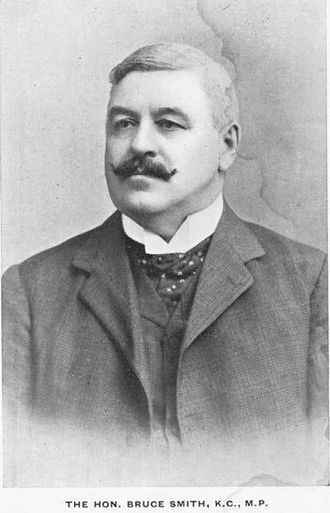

Smith, Bruce. 1887. Liberty and Liberalism. Longmans, Green and Co: London.

[251] Mark…the weighty opinions of M. Leon Say of whom the Times speaks as “the eminent French statesman and economist.” Presiding at a meeting of the Liberty and Property Defence League at Westminster, he said in his address: “The functions of government ought to have well-defined limits, and there are limits which could not be transgressed without entailing misfortunes on mankind. Civilisation itself.” he added, “would be in peril if governments were allowed to go beyond the limits of their natural functions and attributes.” “Liberal economists,” he continued, “were determined to take their stand on the solid ground of observation, and not to deviate from the principles of experimental science. Experimental science showed that human society was a natural fact. Society was not the result of a contract; it was the very condition of humanity.”

Spencer, Herbert. 1888. The Coming Slavery and Other Essays. Humboldt Publishing Company: New York.

[45] Evidently it must be admitted that the hypothesis of a social contract, either under the shape assumed by Hobbes or under the shape assumed by Rousseau, is baseless. Nay more, it must be admitted that even had such a contract once been formed, it could not be binding on the posterity of those who formed it. Moreover, if any say that in the absence of those limitations to its powers which a deed of incorporation might imply, there is nothing to prevent a majority from imposing its will on a minority by force, assent must be given—an assent, however, joined with the comment that if the superior force of the majority is its justification, then the superior force of a despot backed by an adequate army, is also justified; the problem lapses What we here seek is some higher warrant for the subordination of minority to majority than that arising from inability to resist physical coercion.

Donisthorpe, Wordsworth. 1889. Individualism: A System of Politics. Macmillan and Co: London.

[337] Here we have the grand socialist mistake of confounding voluntary co-operation with compulsory. If the whole body of workers were included in one society of their own free will and accord, that would no more be socialism than the present system. It is really time the socialists dropped this absurd contention. Trade unionism is no more socialistic than a [338] joint-stock company or a cricket club. But what is the conclusive reason adduced for discarding voluntary co-operation? Simply that it cannot get rid of competition. So much the better. It must be proved that competition is really the harmful principle in the existing system. That has never been done. It is some comfort to find the wage contract described as a “bargain.” It is usually described by our teacher (J. L. Joynes’s Catechism) and his fellow-socialists as an arrangement forced on the labourer.

Flint, Robert. 1894. Socialism. Isbister and Co.: London.

[405-406] A right constituted by mere need is one which so many may be expected to have that all will soon be in need. Society as at present organised has entered into no contract, come under no obligation, which binds it as a matter of right to support any of its members. It is their duty to support themselves, and they are left free to do so in any rightful way, and to go to any part of the world where they can do so.

William Edward Hartpole Lecky (1838 – October 1903) was an Irish historian and political theorist. In 1896, he published two volumes entitled Democracy and Liberty, in which he considered, with special reference to the United Kingdom, France and the United States, some of the tendencies of modern democracies.

Lecky, William E. H. 1899. Democracy and Liberty, Volume II. Longmans, Green, and Co: London.

[239] Rousseau is more commonly connected with modern communism, but the connection does not appear to me to be very close. It is true that in his early Discourse on inequality he assailed private property, and especially landed property, as founded on usurpation and as productive of countless evils to mankind; but the significance of this treatise is much diminished when it is remembered that it was an elaborate defence of savage as opposed to civilised life. In his later and more mature works he strenuously maintained that “the right of property is the most sacred of the rights of citizens, in some respects even more important than liberty itself;” that the great problem of government is “to provide for public needs without impairing the private property of those who are forced to contribute to them;” that “the foundation of the social compact is property, and that its first condition is that every individual should be protected in the peaceful enjoyment of that which belongs to him.” In the “Contract Social,” however, he maintains that by the social contract man surrenders everything he possesses into the hands of [240] the community; the State becomes the basis of property, and turns usurpation into right; it guarantees to each man his right of property in everything he possesses, but the right of each man to his own possessions is always subordinate to the right of the community over the whole.

Albert Venn "A. V." Dicey (1835 – 1922) was a British jurist and constitutional theorist, and was the younger brother of Edward Dicey. He is most widely known as the author of An Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1885). Dicey popularised the phrase "rule of law", although its use goes back to the 17th century.

Dicey, Albert Venn. 1905. Lectures on the Relations between Law & Public Opinion in England. Macmillan and Co: London.

[263] According as legislators do or do not believe in the wisdom of leaving each man to settle his own affairs for himself, they will try to extend or limit the sphere of contractual freedom. During the latter part of the nineteenth century the tendency to curtail such liberty becomes clearly apparent.

Spencer, Herbert. 1910. Social Statics: Together with Man versus the State, abridged and revised. D. Appleton and Co.: New York.

[300] As we have seen Toryism, and Liberalism originally emerged, the one from militancy and the other from industrialism. The one stood for the regime of status and the other for the regime of contract—the one for that system of compulsory co-operation which accompanies the legal inequality of classes, and the other for that voluntary co-operation which accompanies their legal equality; and beyond all question the early acts of the two parties were respectively for the maintenance of agencies which effect this compulsory co-operation, and for the weakening or curbing of them. Manifestly the implication is that, in so far as it has been extending the system of compulsion, what is now called Liberalism is a new form of Toryism.

Sumner, William G. 1911. War and Other Essays. Yale University Press: New Haven.

[233] There is no time when a man is more supremely sovereign and independent than when he is making a contract, for then he is freely subjecting himself to conditions which he considers [234] satisfactory, for purposes which he considers worth obtaining. It is only another of the confusions which have been introduced into this subject that a juggle is made here on the word “free.” It is declared that the contract is not free, because it is made under the existing conditions of the market, which may be hard for one the parties—an objection which is entirely irrelevant, since the only “freedom” which can here come into account, where the proposition is to use civil and social coercion, is civil and social freedom. If, then, a man is making a contract, how can anybody else judge for him what conditions he shall submit to or what ends he ought to consider worth attaining? His final and perfectly conclusive answer is: I will, or, I will not.

Sumner, William, G. 1914. The Challenge of Facts and Other Essays. Yale University Press: New Haven.

[96] It is sometimes said to be a shocking doctrine that the employee enters into a contract to dispose of his energies, because this would put him on the same plane with commodities. This objection has been current amongst the German professorial socialists for years, and it has recently been made much of here by those who catch eagerly at the sentimental aspects of this subject. Every man who earns his living uses up his vital energy. He may till his own land and live on his own product, or he may raise a product and contract it away in exchange for what he wants, or he may contract away his time, or his productive energies, or “himself,” for the commodities that he needs for his maintenance. In the first case, there is no social relation at all. In the last two cases, no distinction can be made affecting the dignity or the interests of the man which is anything more than a dialectical refinement. The lawyer, doctor, clergyman, teacher, and editor each makes a commodity of himself just as much as the handicraftsman does; each renders services that wear him out each takes pay for his services; [97] each is “exploited” just as much by those who pay as the handicraftsman is. We men have a way of inflating ourselves with big words on this earth, as if we thus gained dignity or were any the less bound down to toil and suffering. If wages were abolished, or if the socialistic state were established, not a feature of the case would be altered. Men would be worn out in maintaining their existence, and the only question would be just what it is now: Can each one get more maintenance for a given expenditure of himself by living in isolation, or by joining other men in mutual services?

[195] If a man, in the organization of labor, employs other men to assist in an industrial enterprise, it was formerly [196] thought that the rights and duties of the parties were defined by the contract which they made with each other. The new doctrine is that the employer becomes responsible for the welfare of the employees in a number of respects. They do not each remain what they were before this contract, independent members of society, each pursuing happiness in his own way according to his own ideas of it. The employee is not held to any new responsibility for the welfare of the employer; the duties are all held to lie on the other side. The employer must assure the employed against the risks of his calling, and even against his own negligence; the employee is not held to assure himself, as a free man with all his own responsibilities, although the scheme may be so devised that the assurance is paid for out of his wages; he is released from responsibility for himself. The common law recognizes the only true and rational liability of employers, viz., that which is deducible from the responsibilities which the employer has assumed in the relation. The new doctrines which are preached and which have been embodied in the legislation of some countries, are not based on any rational responsibility of the employer but on the fact that the employee may sometimes find himself in a very hard case, either through his own negligence or through unavoidable mischances of life and that there is nobody else who can be made to take care of him but his employer.

William Joseph ("Wild Bill") Donovan (1883 – 1959) was a United States soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat. Donovan is best remembered as the wartime head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency, during World War II. He is also known as the "Father of American Intelligence" and the "Father of Central Intelligence".

Donovan, William J. 1936. “The Constitution as the Guardian of Property Rights,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 185(May): 145-153.

[153] The position of those who work for wages is no different. Their liberty of contract, which is the right to work at whatever occupation and for whatever employer they see fit, and to leave his services when greater opportunities open in other lines of work, is essentially a property right. The wage earner has a vested interest as well in stable currency and a balanced government budget which is necessary to such a currency, in order that the savings he counts upon to protect him in times of illness and in old age may not be destroyed.