Liberalism › Rejoinders

Brabourne, Lord. 1882. “The Liberal Party,” Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine 144(888): 542-559.

[542-543] It must be admitted that the so-called Liberals gained a distinct advantage from this nomenclature; for whilst the name of an individual has no special significance of its own, there is something in the word Liberal which, apart from party, recommends itself to men's minds as descriptive of generous and sympathetic feeling, and is likely at once to gain approval from those who are captivated by words without pausing to consider their full sense and meaning. For of course, the truth is, that the word Liberal, as applied to a political party, cannot and does not mean that within the ranks of that party alone are to be found men who are Liberal in the best and non-political meaning of the word. … It is, indeed, beyond controversy that the term Liberal is a misnomer at this moment as applied to any special party or the followers of any particular leader. … That such men as the latter should monopolise, or in fact lay any claim at all to, the term Liberal, is in itself an absurdity at which we could afford to laugh, if it were not that by so doing they conceal their own ends and objects, and, fighting under a name which by no means conveys to the public their true sentiments and ideas, obtain an influence and importance far greater than is warranted by their character and talents.

[544] The term Liberal has been too useful, and remains too attractive, to be lightly abandoned by those who find their advantage in its use; and it will probably be some time longer employed to designate all those multitudinous sections of a party which has little or no cohesion upon any definite principle, and certainly no monopoly of really Liberal principles.

[549-550] If these are the only reforms which Mr. Atherley-Jones claims to be the object of the new Liberalism, not only need we congratulate ourselves upon their moderation, but we may point out that the present Government has already travelled some way upon the same road, and that such reforms required no new party, and the desire to effect them can be monopolised by no new combination, whether it adopts the word Liberalism or any other prefix to the description of its policy and intentions. These ideas are ‘liberal’ in no party sense, they are ‘new’ in no sense at all….

[553] It should, moreover, be noted, that this new Liberalism, into which the Liberalism of former times is invited to merge, is a Liberalism which for every turn belies its own name by imposing restrictions upon everybody, and restraining freedom of action in the most ordinary transactions of life. … So far, then, as we can judge from a partial investigation of the doctrines of the new Liberalism, it seems very probable that old and genuine Liberalism, party and principles together, will presently be doomed by this product of democracy, which, in usurping the name, has abandoned the principles of the real Liberal party. To emancipate trade; to make commerce free; to war against the abuse of privilege; to unfetter the press; to promote religious equality and uphold the principles of liberty in every department of the State, — these were the objects which the Liberal party formerly advanced as those which constituted its programme, and on behalf of which it fought and won its battles in the days which we have left behind us. But those who aspire to lead our new democracy have an altogether different creed. Liberty to them is no reality, but only a political catchword with which to delude the masses into the support of projects which are opposed to its true spirit. It is not liberty but licence which they really desire, —licence for the many to plunder the few; licence for the idle, the thriftless, and the unsuccessful of mankind to prey upon the property of the industrious, the thrifty, and the prosperous. The Liberal party, under the guidance of Mr. Gladstone, has already drifted far enough from its old principles to have forfeited all claim to its distinctive nomenclature.

Pembroke, Lord. 1883. “Liberty and Socialism,” National Review 1(May): 336-361.

[336] The admirable maxims which a generation ago were the watchwords of Liberalism, are disappearing with an alarming rapidity from the minds of men. Long after the Prime Minister entered Parliament one of the chief notes of instructed Liberalism was [a generation ago] the dogma, that the best Government is that which interferes least with social affairs.

Anonymous. 1885. Hints to Country Bumpkins, by a Country Bumpkin. Hatchards, Piccadilly: London.

[3] A ‘Conservative’ at the present day is a man who hates meddling with individual liberty, and wishes to preserve what is good and reform gradually what is bad. All sudden changes cause misery in proportion as they are great and sudden. A ‘Liberal’ used to mean a man who was in favour of reforming what wanted reforming. At the present time it means a Radical, a Socialist, and a Revolutionist. In revolutions all men suffer, but the wage-earners die of starvation.

[4-5] Till five years ago a Liberal meant a man who loves liberty, even though he knows that where there is liberty there cannot be equality. … Now, this liberty the Liberal of the present day wishes to destroy in order to get equality. … The Liberal now is a traitor to liberty. He is a renegade. He has gone over to the enemy. Therefore your election cry ought to be, ‘Liberty for ever, and down with Socialism!’ Socialism means tyrannical meddling. A Liberal, a Radical, a Socialist, and a French Jacobin, mean the same.

[27] Whatever Liberalism has meant it means now French Socialism, to be brought about by universal suffrage.

[46] It cannot be too often repeated that Socialism or the Liberalism of the present day means, in its essence, attacking ownership of property.

[78] Socialism and Radicalism, or the Liberalism of the day, aims at theft from capitalists. You have saved a bit of money, bought an acre of land, and let it for two pounds a-year. Then you are a land-owning capitalist, and your property, or the two pounds a-year income from it, is, according to Mr. H. George and the Socialists, to be stolen from you. They do not call it stealing; they call it ‘expropriating without compensation.’ But this makes no difference.

[95] ‘The individual liberty,’ says Herbert Spencer, ‘and independence of Englishmen as distinguished from the subjection to official control of Continental nations, are signs of our more advanced social state.’ Thus our French Socialists (the Liberals of the present day) are retrogressionists, who want to bring us back to the Continental condition. The Socialist is simply a despotic tyrant of the old-world kind, though he goes by new names. … Such is Socialism, or modern Liberalism.

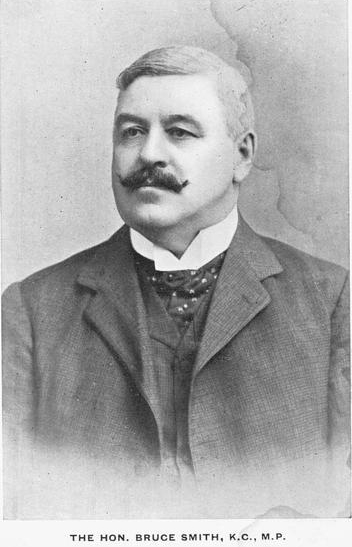

Smith, Bruce. 1887. Liberty and Liberalism. Longmans, Green and Co.: London.

[679] I have, in the first place, shown that, in our own day, the term ‘Liberalism’ has altogether ceased to convey the meaning which attached to it, as a political term, during its earlier currency—that is to say, freedom for the individual. I have shown, further, how, in the present day, that, and other terms, each of which originally signified some tolerably distinct political policy, have had attached to them meanings as numerous as they are contradictory—all of which confusion has arisen from a neglect to regard first principles, and a vain desire to protect human nature from its own ineradicable infirmities, by means of ill-digested and impracticable legislative schemes, calculated to prevent the fittest from making greater progress than is achieved by the unfittest of their kind. I have shown how, by the application to such schemes of terms otherwise favourably associated, much that is in itself unjust and retrogressive has passed among the thoughtless as sound and desirable. That the term ‘Liberalism,’ and the preceding political party titles, for which, as I have shown, it served as a substitute, did involve the principle of liberty for the individual, as opposed to the trammels of a despotic form of government —whether of the monarch or of an aristocracy—I have…demonstrated.

[680] In striking contrast with the growth of civil freedom, and the spirit of true Liberalism in historic times, I have shown how vain were the occasionally well-meant, but ignorantly conceived attempts to increase the national prosperity, by means of legislative interference with the various human activities of a progressive people.

King Jr., Joseph. 1889. “Notes from England,” Andover Review 11(64): 433-437.

[434] This proposal to erect dwellings for the poorer classes by compulsorily buying out the rich owners and levying a tax over all ground values in London, to bear the expense, is a proposal which would have greatly shocked our old economists of the laissez-faire school, and which smacks terribly of Socialism. This, indeed, cannot be denied that the proposals of the Liberal party become more and more socialistic as years roll on; at the same time, the party of avowed Socialists is making great strides, and signs are not wanting that erelong the Socialists will be strong enough to make themselves an important factor in all popular elections.

Spencer, Herbert. 1892. “From Freedom to Bondage” in A Plea for Liberty: An Argument against Socialism and Socialistic Legislation edited by Thomas Mackay. John Murray: London.

[19] Were it needful to dwell on indirect evidence, much might be made of that furnished by the behavior of the so-called Liberal party—a party which, relinquishing the original conception of a leader as a mouthpiece for a known and accepted policy, thinks itself bound to accept a policy which its leader springs upon it without consent or warning—a party so utterly without the feeling and idea implied by liberalism, as not to resent this trampling on the right of private judgment which constitutes the root of liberalism—nay, a party which vilifies as renegade liberals, those of its members who refuse to surrender their independence.

Fisher, F. V. 1894. “Social Democracy and Liberty,” Westminster Review 141: 651.

[651] …[T]he old individualistic Liberalism is threatened by a torrent of socialistic and democratic legislation which may indeed sweep away many abuses but which may also bring in its tide a mass of cumbersome and despotic restrictions.

Flint, Robert. 1894. Socialism. Isbister and Co.: London.

[48-49] [Socialism] owes far more of its success, however, to having appropriated, under the guise of ‘proximate demands,’ ‘measures called for to palliate the evils of existing society,’ ‘means of transition to the socialistic state,’ and the like, the schemes and proposals of the Liberalism or Radicalism which it professes to despise. All these it claims as socialistic, and presents as if they were original discoveries of its own. It has thus put so-called Liberalism and Radicalism to a serious disadvantage, and greatly benefited itself. The result is not yet so apparent in the disorganisation and weakening of Liberalism or Radicalism in Britain as in Germany, but it can hardly fail to manifest itself. In its real spirit and nature, of course, Socialism is more akin to Protectionism of the Paternal State type than to Liberalism. Hence there are various shades and degrees of what is known as State Socialism.

Dicey, Edward. 1894. “The Chamberlain Coalition Programme,” The Nineteenth Century 35(205): 367-378.

[373-374] The truth is that the Home Rule Bill of 1886 was the symptom, quite as much as the cause, of a long-standing divergence of view between the new Liberals and the old. The Repeal of the Union, in obedience to the agitation set on foot by Mr. Parnell, whether vise or unwise in itself, was utterly out of harmony with all the principles on which the Liberals as a party had acted previously. Its acceptance signified the triumph of a new school of Liberalism, which looked with contempt on the old-fashioned doctrines of its predecessors. If the rupture between the old and the new Liberals had not taken place on Home Rule, it must infallibly have taken place on some similar issue, though possibly the secession might then have been less numerous and less simultaneous. Sooner or later the split had got to come. It is quite foreign to my purpose to discuss now whether the old or the new Liberals were in the right. All I wish to point out is that the divergence of opinion extended far beyond the narrow limits of Home Rule. We— if I may be allowed to speak as a pre-Gladstonian Liberal—had no wish whatever to change our Constitution; we were anxious that all the great reforms consistent with the maintenance of that Constitution had been already well- nigh accomplished. We believed in individual liberty, in the freedom of contracts, in the sanctity of property, in the superiority of private enterprise to State intervention, in the supremacy of the law, and in the right of everybody to do what he thought fit, so long as that supremacy was not assailed. We may have been a set of political dodos. That is not the question. All I assert is that such, rightly or wrongly, was our political creed; and it is not surprising that we should have been alarmed when we discovered that the whole policy of the new Liberalism was based on principles antagonistic to every article of our old faith. Even before Home Rule was proclaimed to be the dogma of latter-day Liberalism we had begun to doubt whether we would follow much further in the paths of Radicalism.

Dicey, Edward. 1895. “The Rout of the Faddists,” The Nineteenth Century 38(222): 188-198.

[191] It is not so much that the masses have become Conservative as that they have lost their faith in Liberalism. Nor is it difficult to explain how this should have come about. The British public, irrespective of party names and differences, are averse by instinct to extreme measures and revolutionary changes, they are indifferent to the carrying out of abstract principles to their logical results, they have an innate preference for compromises, they are always inclined to let well alone, and, though they wish abuses to be reformed, they prefer their reforms to be carried out bit by bit and step by step. If this view of English commonplace political sentiment is correct, it is intelligible why the attitude of the new Liberalism should of late years have alienated the sympathies of the ordinary public. When Mr. Gladstone returned to office in 1885, after the agitation excited by the Bulgarian atrocities, the series of great Liberal political reforms which were compatible with our existing constitution had practically been exhausted. The country was not in the mood for any important further advance in the direction of democracy, and wished, in as far as it formulated any distinct desire, to rest and be thankful.

Donisthorpe, Wordsworth. 1895. Law in a Free State. Macmillan and Co.: London.

[307-308] ‘Liberal’ was first used in a political sense about 1815, to denote the advocates of liberty as opposed to the ‘serviles’ who believed in State control. And yet the members of the club avowedly uphold State interference in all things, and dub the doctrine of laissez faire the creed of selfishness. Still the building is a fine and commodious one, and what’s in a name, after all?

Anonymous. 1897. “The Political Transformation of Scotland,” The Quarterly Review 185(369): 269-293.

[288] Mr. Keir Hardie sees indeed no hope for the reunion of the Liberal Party save in the acceptance of Socialism as its guiding principle or pervading force.

‘The Temperance question, standing as a separate issue, arouses as much antagonism as it brings support. The attack on the Established Church does the same. And before the people can be united, some new principle must be raised to attract them. The Independent Labour Party claim that this principle is found in Socialism.’

Nothing could be clearer than this declaration. Mr. Keir Hardie has raised the flag of the Social Revolution, and carries it into every constituency where there happens to be a vacancy. It is not at all improbable therefore that Scotland may supply in the future, as it has often supplied in the past, a valuable object-lesson for the United Kingdom as a whole. … Confronting it is the Party of the Social Revolution, which may not be powerful in numbers at the present moment, but which professes to be drawing recruits from all quarters, and proclaims that it will not rest until it has made Socialism the dominant principle in Liberalism.

MacPherson, Hector. 1899. Adam Smith. Edinburgh: Oliphant Anderson and Ferrier

[116-117] [In 1897] the number of workpeople employed in private establishment who secured the adoption of the eight hours’ day more that equalled the number for the previous four years. If, then, such satisfactory progress is being made in this direction, where is the necessity for the intervention of the State? Such interference could not be applied all round, and it would hamper the natural developments which are now taking place. These Board of Trade statistics are a practical endorsement of the theory on which the old Liberal based their faith—namely, that freedom for the people to work out their own salvation is the true path of progress.

Macpherson, Hector Carsewell. 1900. Spencer and Spencerism. Doubleday, Page and Co.: New York.

[164-166] Government ‘is nothing more than a national association acting upon the principles of society’—a definition very different from the one given by those who deny the rights of man, namely, that society is the creation of government and needs to be regulated by paternal methods. In their practical results these opposing theories may be studied in the Old and New Liberalism.

About the time of the French Revolution, Liberalism underwent an important change—a change which Burke was the first to detect. Rousseau shifted the foundation of Liberalism from natural rights to political rights. According to the French thinker, the fundamental right of man was not the right to liberty, but to an equal share in the government of the country. The people in the exercise of their political rights being in the majority were sovereign; what, and only what, they legislatively declared to be rights were treated as rights. The hitherto accepted natural rights (liberty and property) could be annihilated by the fiat of the all-powerful majority. It is this French theory of political thought which has passed into British politics under the name of the New Liberalism. According to the Old Liberalism, every man has a right to his own property; according to the New Liberalism the majority have a right to encroach upon other people’s property in order, as Mr. Chamberlain’s ‘Radical programme’ puts it, to increase the comforts and multiply the luxuries of the masses. The Old Liberals would have spurned such an interpretation of their creed. In their view, justice and liberty had nothing to do with majorities and minorities. They fought against slavery, not because it was supported by a powerful minority, but because slavery was a violation of the fundamental right of man to personal liberty. The Old Liberals fought for toleration, not on the majority principle, but on the principle that no power on earth had a right to interfere with liberty of conscience. The Old Liberals advocated an extended franchise, not in order to shift absolute power from the classes to the masses, but in order to give every citizen the power to protect his interests. In other words, with the Old Liberals an extended franchise was meant to be a safeguard, not an engine of oppression. The Old Liberals strove to secure for every man equality of opportunity; the New Liberals are striving to procure equality of conditions. They tell Lazarus, who has been sitting at the rich man's gate, to take his place boldly at the rich man's table. In Australia the New Liberalism has borne its logical fruit. Some years ago, at a meeting in Sydney of the unemployed, one speaker demanded that the Government should give as a right, not as a favor, six shillings a day and guarantee work for twelve months. He further advised the unemployed not to submit to insults to their independence. On the principles of the New Liberalism there is nothing to prevent the unemployed, if they are in the majority legislatively, dividing the wealth of the country among the masses. The passion for equality when divorced from the passion for justice becomes a potent instrument of national demoralization. On one occasion, when Turgot was asked to confer a benefit on the poor at the cost of the rich, he replied: ‘We are sure to go wrong the moment we forget that justice alone can keep the balance true among all rights and interests.’ France forgot that, and went terribly wrong. The Liberal party of the present day is in danger of making the same fatal mistake.

Godkin, Edwin Lawrence. 1900. “The Eclipse of Liberalism,” The Nation 71(April 9): 105-106.

[105] These eighteenth-century ideas were the soil in which modern Liberalism flourished…. Rulers were to be the servants of the people, and were to be restrained and held in check by bills of rights and fundamental laws which defined the liberties proved by experience to be the most important and most vulnerable.

[105] To the principles and precepts of Liberalism the prodigious material progress of the age was largely due. Freed from the vexatious meddling of governments, men devoted themselves to their natural task, the bettering of their condition, with the wonderful results which surround us. But now it seems that its material comfort has blinded the eyes of the present generation to the cause that made it possible. In the politics of the world, Liberalism is a declining, almost a defunct force.

[105] …[T]here is a faction of so-called Liberals who so little understand their tradition as to make common cause with the Socialists. Only a remnant, old men for the most part, still uphold the Liberal doctrine, and when they are gone, it will have no champions.

[105] Nationalism as the sense of national greed has supplanted Liberalism. It is an old foe under a new name.

Fremantle, H. E. S. 1900. “Liberty and Government,” International Journal of Ethics 10(4): 439-463.

[446] But certainly [Gladstone’s] remark is notable as marking a change. The change is this, that whereas the old Liberals strove to reduce the restrictive powers of the government, the new Liberalism, when in office, has gone far beyond this, and has conceived the idea of legislating for the positive benefit of its subjects in a manner almost comparable to that of the ancient Athenians. It clears open spaces, it removes uninhabitable houses, it educates children, it constructs public works, it carries our letters, and it sometimes even attempts to build houses for artisans. Now in all this it is taxing some of its citizens at its own pleasure, regardless whether they like it or not, for the benefit of themselves or others; and it is therefore building up new restrictions, for taxation is a restriction of the individual’s liberty to spend his income as he chooses. Nor is this all; it establishes a church, and thereby, according to Mr. Herbert Spencer, compels citizens to support a theological system of which they may disapprove. It interferes with natural competition by patronizing the colleges of physicians and of surgeons; it directly violates personal liberty by compelling house-builders and others to observe the laws of sanitation, and it threatens to surrender to the ever-increasing demands of medical men for the state enforcement of the particular nostrum of each, often only purchasable at the cost of a flagrant infringement of individual freedom. And all this in the name of liberty.

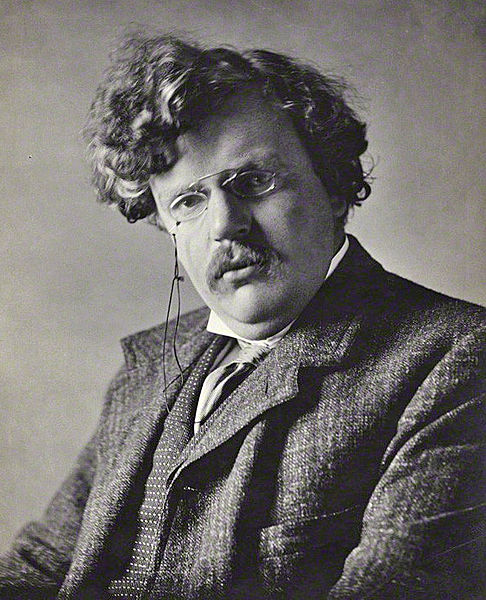

Chesterson, G. K. 1905. “The Poetic Quality in Liberalism,” The Independent Review: 53-61.

[56] Liberalism is a vague word, because it is a good word; but recent and unfortunate events have made it a much vaguer word than it need in any case have been. In current and recent English politics, indeed, the word Liberalism is not so much vague as definitely self-contradictory. … And here we are brought face to face with a difficulty, which has by most people perhaps been only dimly felt, but which I think most politicians have felt so keenly that they spent all their time in passionately denying its existence. It seems to me totally futile and absurd to deny any longer that Liberalism in our time means, not only two different things, but two mutually exclusive and directly antagonistic things. An enlightened Liberal Imperialist, with a theory of Empire, is not a weaker Liberal than I; nor am I a weaker Liberal than he. I am not a paler shade of his blue; he is not a pinker tone of my red. He means one thing by Liberalism; and, in the light of that, legitimately considers me no Liberal at all. I mean another thing by Liberalism, and, in the light of that, legitimately think him no Liberal at all. The difference is not a difference of opinion upon some temporary war or some twopenny tariff. It is a difference of opinion upon the whole meaning of a word; I might say upon the whole meaning of a world. Like all practical things, it goes down into the chasms of metaphysics. Like all urgent things, it demands, first of all, a discussion on Hegel and Plato and the Nature of Being. We may or may not find it possible to effect a political alliance between the two sides; but the alliance would be as purely political as that between Irish Catholics and English Nonconformists. Even if the Imperialist Liberal and the Nationalist Liberal were of the same Party, they must always be of different religions.

[59] When Liberalism met its great debacle, there were, necessarily, two kinds of critics left in the defeated army, with two different plans of campaign, indeed, with two different conceptions of the nature of war. The first formed the coherent and philosophical Liberal Imperialist Party, now consisting entirely of Mr. Saxon Mills; the other formed the Party of which I am a humble member. The first said: ‘The French Revolution succeeded, because it was progressive, because it was the fresh and forward thing at that moment.’ The second said: ‘The French Revolution succeeded because it was religious, because it gave a key or principle which cannot grow old.’ The first said: ‘The old Liberals won, because they were men of their [60] time.’ The second said: ‘They won because they were men of all time; or rather, because the ideas they dealt with are outside time altogether.’ The first said: ‘Old Liberal ideas conquered because they were new: but they are new no longer.’ The second said: ‘Not so. Old Liberal ideas conquered because they were true. And they are true still.’

Anonymous. 1912. “The Interpreter’s House,” The American Magazine 73(5): 635-640.

[636-637] Liberalism!—how the word is mooted and bandied among us! Liberalism is quite the rage just now, and we all freely call ourselves liberals of one kind or another. We go in for liberal politics, liberal religion, liberal journalism, and what we do not go in for we flirt with. But what is liberalism? In politics, for instance, does it imply a party and party machinery such, say, as the Insurgents have? Does it mean following a leadership like that of Mr. Roosevelt or Mr. Wilson or Senator La Follette? Is it defined by a set program like regulation of monopoly, municipal home rule, popular senatorial elections and so forth?

[637] We construct programs and policies, call them liberal, make them the test and touchstone of liberalism, believe in them fanatically and for the most part serve them very illiberally—and presently the Time-Spirit touches them and we see that they were, after all, far from being the heart and core of liberalism. … Well, one thinks at once of the liberalism of [Gladstone’s] time—free trade, home rule, disestablishment, the abolition of church-taxes, and marriage with one’s deceased wife’s sister! What a grotesque idea, one says, to call all this by the august name of liberalism!

Brett, Oliver. 1921. A Defense of Liberty. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[64-65] Liberals believe in democracy, not as an end in itself, but, as Mill said, ‘the best available device for our present political condition.’ They believe in it because it is not Static like Socialism, but has a tendency towards increasing the liberty of the individual from the yoke of opinion and of law. They know that to a certain degree State interference with the liberty of the individual is at this time inevitable; but they desire to keep that degree as small as possible, and to make it ever smaller, instead of building up a system from the embraces of which the individual can never escape. Mill thought that the fruition of all progress was the expansion of the individual nature and the individual personality, free from every possible restraint and pressure; from every invasion and intrusion. It is because the Static State of Socialism holds out no hope of that fruition that Liberalism is bound to oppose it.

[88] Democracy has shown in its short history a tendency towards that freedom which it is the business of Liberalism to encourage. But Democracy, like Christianity, or any other Liberal movement, runs the danger of solidifying into a system and of losing its impetus towards freedom. German philosophers have put the snare of a Static State before its feet. German philosophers have tempted it with the poisonous fruit of organized power. German philosophers have mystified it with the golden idol of the State. It is the work of Liberalism to see that Democracy does not fall a victim to the Conservative decadence which must always be the result of idolizing the State.

[150] Democracy has, in spite of its name, just as much tendency to divide into Liberal and Conservative Parties as any other repository of political power, and those who wish it to take a Conservative direction will, as they have in the past to others, tell Democracy that it can do no wrong. By use of the catchwords of liberty and progress they will try and convince the unlettered majority, first that the philosophers have discovered in Socialism the panacea of all evils, and then that the bureaucrats who are to run that scientific system are merely the obedient servants of Democracy. Just as patriotism was in the past the moral incentive by which men were made the tools of Conservative Imperialism, so in the future Liberty, Fraternity, and Equality are to be the moral incentives of Conservative Socialism. Democracy, like every other political device, has two roads on which it may travel, backwards towards State control, or forwards towards individual liberty. That is the issue between the Conservative and the Liberal mind. It is the business of Liberalism to see that Democracy makes the latter its choice.

[210-211] We have endeavored in the preceding chapters to show that Socialism represents the Conservative influence in modern political society. It is made up of all the ingredients of Conservative thought. It is invented by philosophers on the premise of a clean slate. It maintains that Government is a science and not an art. It is grossly materialistic. It denies all natural rights. It creates a Static State, gives it the sanction of patriotism and idolatry, endows it with unlimited power, authority, and control, and, after dividing society into two definite classes, hands over to one of them, and that a natural aristocracy of brains, the unchallenged and permanent possession of the machine. It refuses to wait for the processes of evolution, and, by the very impetus of its own principles, is obliged to follow the path first of national revolution, and then of international war, in order to impose its doctrines. Above all, it possesses a disastrous tendency to decrease the individual liberty of men.

Against systems based upon such ideas Liberalism has been contending since the dawn of history, and the need for it to continue the struggle against the Socialist reincarnation of Conservatism is obvious and vital.

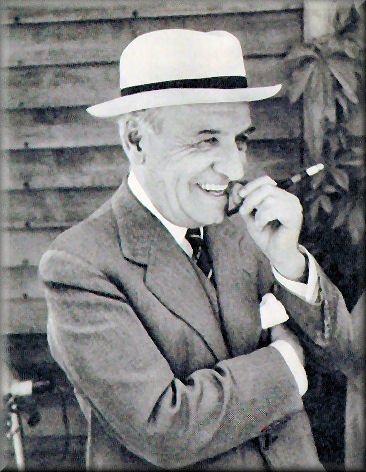

Henry Louis "H. L." Mencken (1880 – 1956) was an American journalist, essayist, magazine editor, satirist, critic of American life and culture, and scholar of American English. He is regarded as one of the most influential American writers and prose stylists of the first half of the twentieth century.

Mencken, H. L. 1925. “Liberty and Democracy” from the Baltimore Evening Sun, April 13. Reprinted in A Second Mencken Chrestomathy, 1995, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

[36] Including especially Liberals, who pretend—and often quite honestly believe—that they are hot for liberty. They never really are. Deep down in their hearts they know, as good democrats, that liberty would be fatal to democracy…. They themselves, as a practical matter, advocate only certain narrow kinds of of liberty—liberty, that is, for the persons they happen to favor. … The liberty to have and hold property is not one that they recognize. They believe only in the liberty to envy, hate and loot the man who has it.

Fish, Jr., Hamilton. 1931. “The Menace of Communism,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 156(Jul.): 54-61.

[55] There is a great misunderstanding in America, largely due to Communists and Socialists and pink intellectuals, who lecture throughout this land and make most of the noise and represent about five percent of the population. They want you to believe that the Communists overthrew the Czar’s regime and that there is some connection between Liberalism and Communism.

Ortega y Gasset, Jose. 1932. The Revolt of the Masses. London.

[83] Liberalism—it is well to recall this today—is the supreme form of generosity; it is the right which the majority concedes to minorities and hence it is the noblest cry that has ever resounded on this planet. It announces that the determination to share existence with the enemy; more than that, with an enemy which is weak. It is incredible that the human species should have arrived at so noble an attitude, so paradoxical, so refined, so anti-natural. Hence it is not to be wondered at this same humanity should soon appear anxious to get rid of it. It is a discipline too difficult and complex to take firm root on earth.

Friedrich August von Hayek, frequently known as F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian, later British, economist and philosopher best known for his defense of classical liberalism. In 1974, Hayek shared the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (with Gunnar Myrdal) for his "pioneering work in the theory of money and economic fluctuations and ... penetrating analysis of the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena."

Hayek, F. A. 1933. “Carl Menger,” Economica 1 N.S.(4): 393-420.

[417] …[Carl Menger] tended to conservatism or liberalism of the old type.

Dunn, Samuel O. 1935. “Modified Laissez Faire,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 178(Mar.): 142-147.

[142] A planned economy, whatever its objectives, must, to be effective, be a government economy, either communist or Fascist. The protagonists of a planned economy, whatever degree of planning they favor, call themselves ‘liberals.’ The word ‘liberal’ came into use to describe one who favored more liberty, for both industry and individuals. The issue with which we are confronted is not of conservative versus liberalism. It is that of state-ism versus liberalism.

[147] I believe that a true ‘liberal’ is still one who believes in the greatest liberty for industry for industry and the individual compatible with the necessary exerciser of governmental power to restrict ‘economic cannibalism’ as much as practical. I agree with Professor Taylor that out utopia should always be, not a planned economy, but laissez faire, although it will always be unattainable because of the necessary activity of government in restricting exploitation; and that, while maintaining democracy, we should strive constantly to restrict government in industry as much as practicable, and restrict politics in government as much as practical, in order that both government and industry may function as efficiently and equitable as practical in both the production of wealth and distribution of income.

This doctrine is Bourbonism and Toryism. It was liberalism once. It will be liberalism again when we have tired of planned economies designed by theorist of the armchair, inexperienced in the realities of either government or industry, and executed by bureaucrats thinking only of politics, or by dictators who have adjourned politics.

Knight, Frank H. 1936. “Pragmatism and Social Action.” International Journal of Ethics 46(2): 229-236.

[231] It is at this point that, as I wish to maintain, Professor Dewey’s theories of liberalism and his program for its salvation go definitely and catastrophically wrong. He seems to confuse the unquestionable fact that scientific and technological knowledge is in a fundamental sense social in genesis and transmission with the view that this style of intelligence is applicable to social problems, which is the antithesis of the truth. What is the matter with liberalism in connection with the use of intelligence is especially the fact that in its view of society it has taken intelligence in the instrumentalistic-scientific sense. This is shown especially in the whole endeavor to build social sciences on natural-science models, and at the same time to view them as guides for, or in any way relevant to, social action. Natural science in the predictive sense of astronomy rests on postulates which exclude the possibility of action in the social field, since this means action of the subject matter on itself; natural science in the ‘prediction-and-control’ sense of the laboratory disciplines is relevant to action only for a dictator standing in a one-sided relation of control to a society, which is the negation of liberalism and of all that liberalism has called morality.

[232] As usual, nothing is said about who is to do the educating of ‘society.’ Presumably ‘we’ are to do it-we reformers, saviors of society. This throws us squarely into communistic, or possibly fascistic, theory, the antithesis of democracy, of freedom, and of any liberalism.

[233] The excessive individualism which is the real threat to liberalism is definitely a modern development, the product of liberalism itself or, more accurately, each has produced the other, or the various aspects of liberalism have evolved in interaction, as is always the case with the major aspects of any cultural form. The real weakness of liberalism is that by taking certain general principles, such as individual freedom and scientific intelligence, too naively and carrying them to extremes, it has educated against itself, against the fundamental conditions of its own permanence.

[236] The really discouraging thing about the position of liberalism in the world is the character of intellectual leadership which is able to secure recognition. Whether we look at philosophy or social science, or radical politics or the labor movement, sound and comprehensive grasp of the nature of social conflicts and problems is hardly to be found in utterances which succeed in making themselves audible or getting into print. Typically, the proposals for action which do get a hearing either do not make sense at all--one cannot imagine them enacted and carried out by free political process--or they are such as would aggravate instead of cure or alleviate the evils at which they are directed.

Chamberlin, William Henry. 1938. Collectivism, A False Utopia. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[179] Faith in the absolute and permanent value of liberalism, under which term I understand not adherence to any special political party, but belief in the programme of liberty…is being subjected to merciless revision on all sides.

Knight, Frank H. 1938. “Lippmann’s Good Society.” The Journal of Political Economy 6(6): 864-872.

[865] The turning-point from liberalism as laisser faire to liberalism as collectivism, miscalled liberalism, is set at about 1870. The current phase of the movement toward collectivism in the United States, as regards the structure and process of government, is the active development of pressure groups under the wing of the government itself, together with the displacement of the activities of legislature and courts by administrative organs and processes. The original liberal movement was, more than any other one thing, a struggle for an effective legal order. Our self-styled liberals of today are doing their utmost to get away from legality.

[865] It might have been thought self-evident, if anything in the field of politics can be called such, that the first essential function and task of government is to preserve unthreatened its own monopoly of political power, and that this means prevention of the development of dangerous power groups outside itself. As against the currently popular version of ‘liberalism’ Mr. Lippmann sees all this and expounds it in noble prose, along with an eloquent plea for the maintenance of liberty through action, in contrast with inaction.

[869] There is a disconcerting amount of truth in this assertion for the defender of historical liberalism as the status quo, while to the true liberal without pre-possessions it is what he would like to believe. Its truth would simplify the problem of freedom enormously. But, stated as Mr. Lippmann states it, it is mere dogma and, to most economists, improbable.

Michel, Virgil. 1939. “Liberalism Yesterday and Tomorrow,” Ethics 49(4): 417-434.

[423] What Dewey here means is nothing less than some kind of socially planned economy that is nation-wide. I mention this only to point out the obvious fact that modern liberals are advocating a system that curtails freedom as previously conceived. But the moment we accept the need of socially enforced restriction on the unqualified attitude of laissez faire, we are facing a new question—that of some standard of judgment other than one of freedom for mere freedom’s sake, or liberty merely conceived negatively as freedom from restriction with no positive directions given in which freedom should tend. This brings up the inevitable question of a system of values however vaguely conceived, a whole philosophy of life for the achievement of which human liberty is a means and instrument.

[431] The purely negative aspect of state or government in the laissez faire era has been abandoned in favor of state regulation, and some who still call themselves liberals have gone so far in their advocacy of this as to give up apparently the very ideal of personal liberty.

Nock, Albert Jay. 1943. Memoirs of a Superfluous Man. Harper and Brothers: New York.

[124] Herbert Spencer’s essays, published in 1884, on The New Toryism and The Coming Slavery left me with an extremely bad impression of British Liberalism. Since 1860, Liberals had been foremost in loading up the statute-book with one coercive measure of ‘social legislation’ after another in hot succession, each of which had the effect of diminishing social power and increasing State power. In doing so, the Liberals were manifestly going dead against their traditional principles. They had abandoned the principle of voluntary social cooperation, and embraced the old-line Tory principle of enforced cooperation.

Taylor, Overton H. 1960. A History of Economic Thought: Social Ideals and Economic Theories from Quesnay to Keynes. New York: McGraw-Hill. P. 427.

[B]etween this newer 'liberalism' and the kind of compromise or halfway house that 'democratic socialism' appears to have settled into, the difference is not very great. There has been a convergence from both sides toward a common, middle ground--a 'watering down' of democratic socialism in the liberal ('libertarian') direction, and a trend of 'liberal' thought and practice away from adherence to its old laissez-faire tradition, into advocacy of what might be called 'humanitarian big government,' i.e., in the direction of semi-socialism.

Taylor, Overton H. 1960. The Classical Liberalism, Marxism, and the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 6-7.

I do not identify 'liberalism' with the cult of the Rooseveltian New Deal and Harry Truman's Fair Deal, nor with enthusiasm for the trend toward the welfare state or what might be called 'humanitarian big government,' as opposed to the older American tradition in favor of more limited government or laissez faire or 'rugged individualism.' In fact, and in spite of the fact that the views and attitudes of our remaining devotees of that older tradition are now generally described--correctly enough in one sense--as conservative or even reactionary, the old liberal ideal was a society of largely free and ungoverned or only self-governed, independent individuals, living together under and jointly supporting a small, simple, inexpensive government having only a quite limited sphere of authority or a few quite limited powers and functions. This was the original from of what I call the classical liberalism.

Nock, Albert Jay. 1991 [1944]. “Liberalism, Properly So Called” in The State of the Union: Essays in Social Criticism by Albert Jay Nock, ed. Charles H. Hamilton, 276-284, Indianapolis: Liberty Press.

[276] First, why is it that Liberalism is now motivated by principles exactly opposite to those which originally motivated it, and how did this change come about? … The facts are clearly apparent. We now see on all sides the extraordinary spectacle of Liberals doing their best to destroy the cardinal freedoms and immunities which Liberals formerly defended, while all the forces which are historically and traditionally known as Tory or Conservative are arrayed in defense of those freedoms. Furthermore we see liberals vehemently vilify those who hold to the original principles of Liberalism, denouncing them as enemies of society, and doing all they can do to discredit and disable them.

[281] Liberalism in this country never had a political organisation, nor has it ever had anything in common with earlier British Liberalism. It was never formulated in definite terms, even according to the broad original British formula which defined Liberal as “one who advocated greater freedom from restraint, especially in political institutions.” Thus it has had no tradition, unless one might say that it has perhaps come more or less into the degenerate British Liberal tradition of Benthamite and Comtist expediency; but this is no doubt a matter of coincidence rather than design.

[282] Twelve years ago, when a government made up of professing Liberals proposed a large-scale positive bureaucratic intervention to relieve distress, and by use of the taxing-power brought all citizens into enforced cooperation with it, Liberals were in favor of it. They regarded only the immediate end—the relief of distress—and not at all the nature of the means; and the means did actually serve that end, though in a most disorderly and wasteful fashion.

The true Liberal, the Liberal of the eighteenth century, would at once have looked beyond that end and asked the great primary question which finally judges, or should judge, all political action: What type of social structure does this measure tend to produce? Does it tend to improve and reinforce the existing type, or to bring about a reversion to the primary militant type? Does it tend towards advance or retrogression, towards progress in civilisation or towards re-barbarisation?

Mises, Ludwig von. [1944] 1962. Bureaucracy. Yale University Press: New Haven.

[125] The champions of socialism call themselves progressives, but they recommend a system which is characterized by rigid observance of routine and by a resistance to every kind of improvement. They call themselves liberals, but they are intent upon abolishing liberty.

Hayek, F.A. 1947. “Opening Address to a Conference at Mont Pelerin” in Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics by F.A. Hayek (1969), 148-159, New York: Simon and Schuster.

[149] The basic conviction which has guided me in my efforts is that, if the ideals which I believe unite us, and for which, in spite of so much abuse of the term, there is still no better name than liberal, are to have any chance of revival, a great intellectual task must be preformed.

Mises, Ludwig von. [1949] 2007. Human Action, Vol. II. Liberty Fund: Indianapolis.

[284] In the United States, [detractors of genuine liberty] call themselves true liberals because they strive after such social order. … They define liberty as the opportunity to do the ‘right’ things, and, of course, they arrogate to themselves the determination of what is right and what is not. In their eyes government omnipotence means full liberty. … The market economy, say these self-styled liberals, grants liberty only to a parasitic class of exploiters, the bourgeoisie. These scoundrels enjoy the freedom to enslave the masses. … Under socialism the worker will enjoy freedom and human dignity because he will no longer have to slave for a capitalist. Socialism means the emancipation of the common man, means freedom for all. It means, moreover, riches for all.

Hayek, F. A. [1948] 1980. Individualism and Economic Order. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

[2-3] The difficulty which we encounter is not merely the familiar fact that the current political terms are notoriously ambiguous or even that the same term often means nearly the opposite to different groups. There is the much more serious fact that the same word frequently appears to unite people who in fact believe in contradictory and irreconcilable ideas. Terms like ‘liberalism’ or ‘democracy’ or ‘socialism,’ today no longer stand for coherent systems of ideas. They have come to describe aggregations of quite heterogeneous principles and facts which historical accident has associated with these words but which have little in common beyond having been advocated at different times by the same people or even merely under the same name.

[271] …[I]s it too much hope for a rebirth of real liberalism, true to its ideal of freedom and internationalism and returned from its temporary aberrations into the nationalist and socialist camps?

Schumpeter, Joseph. 1954. History of Economic Analysis. University of Oxford Press: New York.

[394] As a supreme if unintended compliment, the enemies of the system of private enterprise have thought it wise to appropriate its name.

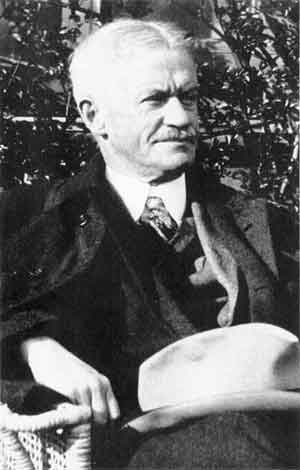

Milton Friedman (1912 – 2006) was an American economist, statistician, and writer who taught at the University of Chicago for more than three decades. He was a recipient of the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, and is known for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory, and the complexity of stabilization policy.

Friedman, Milton. [1962] 1982. Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

[5] As it developed in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth centuries, the intellectual movement that went under the name of liberalism emphasized freedom as the ultimate goal and the individual as the ultimate entity in society. … Beginning in the nineteenth century, and especially after 1930 in the United States, the term liberalism came to be associated with a very different emphasis, particularly in economic policy. It came to be associated with readiness to rely primarily on the state rather than on private voluntary arrangements to achieve objectives regarded as desirable. The catchwords became welfare and equality rather than freedom.

[5-6] The nineteenth-century liberal regarded an extension of freedom as the most effective way to promote welfare and equality; the twentieth-century liberal regards welfare and equality as either prerequisites of or alternatives to freedom. In the name of welfare and equality, the twentieth-century liberal has come to favor a revival of the very policies of state intervention and paternalism against which classical liberalism fought.

Hayek, F. A. 1976. Law Legislation, and Liberty Volume III. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

[44] Legal positivism has become one of the main forces which have destroyed classical liberalism because the latter presupposes a conception of justice which is independent of the expediency for achieving particular results. Legal positivism, like the other forms of constructivists pragmatism of a William James or John Dewey or Vilfredo Pareto, are therefore profoundly antiliberal in the original meaning of the word, though their views have become the foundation of the pseudo-liberalism which in the course of the last generation has arrogated the name.

Hayek, F. A. 1988. The Fatal Conceit. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

[52] This constructivism not only includes the Benthamite tradition…but also practically all contemporary Americans who call themselves ‘liberals.’

Oakeshott, Michael. 1991. Rationalism in Politics and other Essays. Liberty Fund: Indianapolis.

[385-6] If [Henry C. Simons] was a liberal, at least he suffered from neither of the current afflictions of liberalism—ignorance of who its true friends are, and the nervy conscience which extends a senile and indiscriminate welcome to everyone who claims to be on the side of ‘progress’. We need not, however, disturb ourselves unduly about the label he tied on to his credo. He calls himself a liberal and a democrat, but he sets no great store by the names, and is concerned to resolve the ambiguity which has now unfortunately overtaken them.