Equality › Confusions

Holyoake, George Jacob. 1875. The History of Co-operation in England Vol. I. J. B. Lippincott and Co.: Philadelphia.

[3-4] The Co-operation of later days, of which I purpose to write the history in England, begins in mutual help, with a view to end in a common competence. A co-operative society commences in persuasion, it proceeds by consent; it accomplishes its end by common efforts, it incurs mutual risks, intending that all its members shall mutually and proportionately share the benefits secured. The equality sought is not a mad equality of equal division of unequal earnings, but that just award of gains which is proportionate to work executed, to capital subscribed, or custom given. There is equality under the law when every man can obtain justice, however low his condition or small his means; there is equality of protection when none may assault or kill the humblest person without being made accountable; there is civil equality when the evidence of all is valid in courts of justice, irrespective of speculative opinion; there, is equality of citizenship when all offices and honours are open to merit; there is equality of taxation when all are made to contribute to the support of the state according to their means; and there is equality in a co-operative society, when the right of every worker is recognised to a share of the common gain, in the proportion to which he contributes to it, in capital, or labour, or trade—by hand or head; and this is the only equality which is meant, and there is no complete or successful Co-operation where this is not conferred, and aimed at, and secured. Co-operation, after being long declared innovatory and impracticable, has been discovered to be both old and various.

Harris, Alexander. 1877. “Dominion and Subordination, The Normal Relations of Society,” The Mercersburg Review 24(Oct.): 520-543.

[528-529] But is this asserted equality before the law the truth, or is it a delusion; and such a one as entails harm and injury upon those believing themselves benefited by it? …[I]s the poor man equal with the rich man in all other particulars? Can be[1] with equal advantage aspire for political promotion before his fellow-citizens? Between two candidates of equal character and capacities, and of the same political party, but of different wealth and social position, which is almost sure to receive the favor of his neighbors and acquaintances? Is not the rich candidate almost sure to receive the preference? And yet this occurs in a country where all men are declared as equal before the law. When two young men are ready to engage in business, which of them sets out with most advantages? Is it not he who can command his ancestral wealth and large family influence? But if either have the superior advantage, are they equal before the law? They surely are not.

[530-531] Equality before the law, simply imports that the inequalities engraven upon the face of creation shall be entirely ignored in legislation; and that society shall constantly be consigned to chaos, in order that the aristocracy of nature, rather than any other kind, may be able to hold in slavery its subordinates. Like the umpire with closed eyes, within an amphitheatre, the law sits and deceptively says to the contestants, great and small, weak and powerful, ‘Ye are all equal;’ but the result soon demonstrates that the strong and athletic ever carry away the victory. The law in seeming to accord to all classes what is called equality, oversteps its power; for its non-interference in the contests of life allows as great inequality to obtain as did under former systems. It stands the indifferent spectator, and permits all kinds of wickedness, crime and dishonor to become factors in the struggles for superiority. In doing so, slavery is by no means eradicated; but a baser class of masters rise to the places of authority, than could do so under the older forms of social existence. Since therefore slavery and inequality are as veritably fixed in the being of modern so-called free society, as existed in former ages; the inquiry most deserving of attention is this: has the world, at length, secured the most just form of subordination attainable; or that in which justice, right and equity may be able to compete to the best advantage with their contrary evils?

Mivart, George. 1879. “The Government of Life,” The Nineteenth Century 5(26): 690-713.

[703] But it is ‘equality’ which has met and meets with the least sympathy and the most opposition from some excellent persons, while from others it has elicited the strongest feelings in its favour. This diverse development of honest sentiment from one apparent cause must be due to an ambiguity. It shows that the supposed one cause is really not one. There is, in fact, equality and equality. There is the equality which honest men hate, the desire for which is prompted by envy, and tends to a revolutionary process of summary levelling, — the equality which results from a desire to be equal to your superiors and superior to your equals; and there is the equality which honest men love, the desire for which is prompted by benevolence, and tends to elevate and to diffuse all benefits as widely as possible—which would diffuse not merely material welfare, but intellectual, aesthetic, and moral good also. In the latter sense ‘equality,’ like the ‘social contract,’ though an absurdity when regarded as something to be immediately realised, is none the less admirable as an ideal for the future, towards the fulfilment of which our most strenuous efforts may be fitly directed. But even this assertion may probably arouse strong opposition on the part of many.

George, Henry. [1879] 1926. Progress and Poverty. Garden City Publishing: New York.

[545] In our time, as in times before, creep the insidious forces that, producing inequality, destroys Liberty… It is not enough that men should vote; it is not enough that they should be theoretically equal before the law. They must have liberty to avail themselves of the opportunities and means of life; they must stand on equal terms with reference to the bounty of nature. Either this or Liberty withdraws her light!

Lorimer, James. 1880. The Institutes of Law. William Blackwood and Sons: London

[375-376] However much the better sort of Englishmen may be satisfied of the practical impediments which stand, for the present, in the way of the attainment of social and political equality, in the popular sense, either in England or anywhere else—nay, however fully they may be convinced of the impropriety of its admission amongst the immediate objects of any scheme of legislation, or system of positive law, in any stage of development which mankind has yet reached, there are, in many honest minds, hazy notions about its absolute justice and ultimate expediency, which cause them to hesitate in dismissing it from the objects of jurisprudence on absolute grounds. They shrink from the consequences which it has involved hitherto, and which apparently it must always involve; and yet, as they can see no logical or scientific escape from it, they arrive at the untenable, irrational, and absurd conclusion, that though wrong in practice it must be right in theory. And it so chances that, if in some degree protected by their national temperament against the extremest practical consequences of the doctrine of equality, Englishmen stand to it, logically, in a peculiarly helpless position.

Craig, Edward Thomas. 1882. The Irish Land and Labour Question. Trubner and Co.: London.

[73] The political economist may urge that the law of supply and demand must be taken into consideration. This is true in the present irrational relations between labour, land, and capital. The object should be to obtain a rule of justice, if we seek the law of righteousness. This can only be fully realised in that equality arising out of a community of property, where the labour of one member is valued at the same rate as that of another member, and labour is exchanged for labour.

Green, Thomas Hill. 1883. Prolegomena to Ethics. Clarendon Press: Oxford.

[289] That change was itself, indeed, as has been previously pointed out in this treatise, the embodiment of a demand which forms the basis of our moral nature—the demand on the part of the individual for a good which shall be at once his own and the good of others. But this demand needed to take effect in laws and institutions which give every one rights against every one, before the general conscience could prescribe such a rule of chastity, founded on the sacredness of the persons of women, as we acknowledge. And just as it is through an actual change in the structure of society that our ideal in this matter has come to be more exacting than that of the Greek philosophers, so it is only through a further social change that we can expect a more general conformity to the ideal to be arrived at. Only as the negative equality before the law, which is already established in Christendom, comes to be supplemented by a more positive equality of conditions and a more real possibility for women to make their own career in life, will the rule of chastity, which our consciences acknowledge, become generally enforced in practice through the more universal refusal of women to be parties to its violation.

Gronlund, Laurence. 1884. The Cooperative Commonwealth. Lee and Shepaud: Boston.

[98-99] That is to say, the commonwealth will be a state of equality.

It is said that ‘we already have equality,’ and when we ask the meaning of the phrase, we are told that all are ‘equal before the law.’ If that were really the case—what it is not—it would be but a poor kind of equality. The cells of the root and of the flower in a plant are ‘equal;’ the cells of the foot and of the heart in an animal are ‘equal,’ for they are all properly cared for; the organism knows of no ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ organs or cells. And so it will be in the future commonwealth; there ‘equality’ will mean that every unit of society can truly say to any other unit, ‘I am not less than a man, and thou are not more than a man.’

Again, our commonwealth will put interdependence in the place of the ‘right’ to life, liberty, and the pursuit of ‘happiness,’ asserted by the American Declaration of Independence. What use is it to possess the ‘right’ to do something when you have not the power, the means, the opportunity to do it? Is this right to the pursuit of ‘happiness’ not a mocking irony to the masses who cannot pursue ‘happiness’? We saw how the millionaire and the beggar would be equally miserable outside of the State, and behold how much this rights-of-man doctrine has done for the former and how very little for the latter.

The future commonwealth will help every individual to attain the highest development he or she has capacity for. It will lay a cover for every one at nature's table. ‘State’ and ‘State help’ will be as inseparable as a piano and music.

Starkweather, A. J. and S. Robert Wilson. 1884. Socialism. John W. Lovell Co.: New York.

[29] Socialism advocates that the time and service of one man is equal ultimately to the time and service of any other man; hence the nearest approach to exact justice is equal pay for equal time and expenditure of equal energy

Bellamy, Charles Joseph. 1884. The Way Out, Suggestions for Social Reform. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[5] But equality in knavery is no equality, within the meaning of that noble word. That is no justice which permits a few lucky or shrewd ones to profit by the loss of the rest, even if all have the same possibility of defrauding the mass of their fellow creatures, if luck and cunning are on their side. We should all be equal in our rights, but equality in the possibility of doing wrong is no equality at all. No one, far less all of us, should have the privilege of defrauding our fellows out of their share of the comforts or luxuries of this world, as must in the nature of things be done when great accumulations of wealth gather in few hands, while the vast majority of the human race are in want of the bare necessaries of existence.

[87-88] So far, then, as the principle of equality in rights applies to the question of the rewards of labor, it means that each workman, whether he be manager or weaver, helper in the picker room, or day laborer outside, has an equal right to what he earns, —a right upon which much of this dissertation is based, —but certainly no right to what another co-laborer earns.

Crozier, John Beattie. 1885. Civilization and Progress. Longmans, Green and Co.: London.

[410] …Between the individual member of the upper classes and the individual working-man there is neither material nor social equality, and therefore neither equality of status nor of social right.

Ely, Richard T. 1886. The Labor Movement in America. Thomas Y. Crowell & Co.: New York.

[97] The economic philosophers of the time [of Adam Smith] believed that legal equality and freedom of contract were the sole conditions needed to enable the working classes to secure a share of the national product of national industry, a share sufficient to serve as a basis for their physical, ethical, and spiritual development. This theory was based on two fallacies,—the first was the assumption of the natural equality of men…. But the equality of men is a chimera.

Graham, William. 1886. The Social Problem in Its Economical, Moral, and Political Aspects. Kegan Paul, Trench, and Co.: London.

[271] But for the operation of this cause tending to dispersion, the inequality of wealth which now exists would have been far more glaring than it is. Every generation the masses are re-divided. The larger masses gathered through a lifetime are broken at the end of the gatherer's life. And there is no primogeniture, unless, perhaps, there be landed estate. The property is divided by the capitalist’s Will amongst sons and daughters according to prevailing sentiments of justice amongst his class.

[371-372] To reconcile private property with equality of wealth is an impossible problem for modern society—impossible in speculation and impossible in practice. But to make some reasonable approach to equality, to bring a little nearer in fortune the widely distant extremes of rich and poor, never so far asunder before, is not only a possible problem but a pressing one, demanding immediate attention in all civilised communities. And it is a political problem chiefly—a problem to be dealt with by statesmen. On all sides, and in all countries, the problem of a better distribution of wealth is acknowledged to be the most important problem of our generation.

[372-373] We can neither have equality of wealth nor equality of opportunity under our present regime of property. An equal start is impossible, unless all had equal education and equal chance of the prizes of life; the former impossible unless the poor were educated, and the pick of them up to the highest standard, at the expense of the community; the latter impossible unless the State were the sole employer of labour and director of industry—unless, in fact, all private enterprise and industry had ceased, and the great businesses made and built up by successive private individuals’ initiative and energies had all passed into the hands of the State—unless, finally, the State not only worked, as it now does, the postal and telegraph service in addition to its other functions, but, further, worked the railway service, the merchant service, the coal mines, the iron mines; was the sole factory owner and mine owner, the sole brewer and distiller, the sole banker and broker;—unless it was all this, and did all this through its own appointed officials and labourers, whom we must; further suppose to be selected by it, whether by competitive examination, or by some other method of finding the fit and the unfit.

[374] Meantime the cry for greater social equality has become a force, and a force that will increase.

[376] Above all, it means the protest of Nature in addition to the social protest—the protest that her inequality of gift—the only natural, the only ineradicable inequality, the only inequality by ‘divine right’—has been nullified and overridden and trampled on by society’s artificial inequality; that the one inequality founded on fact, on reason, and on justice, has been set aside by another founded on chance or chicane in the present, very often on force or fraud in the past, and in both cases favoured by existing laws and institutions.

Politicus. 1886. New Social Teachings. Kegan Paul, Trench, and Co.: London.

[55-56] Let us, then, without further delay, agree with the contenders for a ‘just price,’ that prices may be wrong morally as well as commercially; and that, therefore, prices may be right or just. This being so, the further agreement is at once implied that exchange at a just price is desirable. But what is a just price? … Equality, then, is the rule of just exchange. By it each man has his own.

Bemis, Edward W. 1886. “Socialism and State Action,” Journal of Social Science 21: 33-68.

[33] Shall we call him a socialist who wishes to introduce more justice and equality in the distribution of wealth? Then must every social reform be thus designated. The socialism of to-day, as distinct from that of Fourier and Robert Owen of fifty years ago, is more than this. … If we accept Marx, Hyndman and Gronlund as true interpreters of our theme—and who denies them that distinction?—the concentration of all means of production in the hands of the State must be considered the essential feature of modern socialism. We may, then, define socialism as the attempt to introduce greater equality and justice into social conditions through State ownership of the means of production.

[46] Scientific State socialism recognizes our competitive system of industry as a necessary stage in a progress from private ownership of the person, or slavery, which alone could give the privileged few sufficient leisure to develop art, literature and all we call civilization, through the present form of private ownership of capital, or the instruments of production, to the future of private property only in income. … In no other way, it is admitted, could the improvements in production of the present century have been possible, but it is claimed that the problem of the creation of wealth having now been solved, it is both possible and wise to pass on to the next stage in the evolution of society where a more equitable distribution of the benefits of wealth and civilization may be attempted.

Griswald, Wolcott Noble. 1887. A Consideration of the Wealth and Poverty of Nations. The Bancroft Company: San Francisco.

[48] The failure of the doctrine of equal rights to produce equality of condition or possessions cannot therefore be traced largely to inequality as to personal want, capacity or power. Other causes which have resulted in marked inequalities, everywhere notable— massed wealth on the one hand, galling poverty on the other—exist and must be assiduously and conscientiously sought. The rights of persons descend of necessity to the material things about them; rights to use, or ownership, or both combined. The causes of marked inequalities referred to, are to be sought in an unequal distribution of the objects of these rights, in the failure of each person to secure use or ownership in the opportunities, franchises and facilities of industrial life; failure engendered by an erroneous and vicious system of appropriation and investiture.

Bascom, John. 1887. Sociology. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[44-45] The principle of equality aims at this liberty, and is just, so far as it is necessary to it, and good, in so far as it reaches it. Equality, however, as an arbitrary, absolute factor, would destroy all combination, and so destroy its own value. Liberty is for the sake of combination, and equality, in the potentialities which society confers, is for liberty. All combination tends to become fixed, and so to destroy farther combination. Liberty, equality resist this tendency, and renew day by day the conditions of farther growth. Thus many of our states revise their constitutions from time to time to admit fully into the fundamental law new conditions. A race that is fair demands an equal start. The race itself destroys at once this equality of advantages, and a series of races must renew it. As new competitors appear, or old competitors seek a new trial, the games are restored by restoring their first terms. A wise state must concede a certain concentration of power. To deny this accumulation of power is to refuse organization, and so take away the promise of growth. The state must also by every just device restore the conditions of renewed organization, and prevent the past from preoccupying and controlling the present. This is the very difficult task of government. In this movable equilibrium the justice of to-day becomes the injustice of to-morrow. The interests of the community demand a constant transfer of advantages from competitor to competitor. The watchful eye of the state must be directed for protection to all classes of persons who are likely to lose ground by their own weakness, and so be permanently thrown out of the ways of advancement by the simple force of events. The wise physician strives to quicken the dormant members of the body, and to quiet the activity of the fevered ones.

[233] When the capitalist can say to the laborer, ‘Do this or quit; take these wages or leave them; it matters not to me, I run my own business,’ we have all the requisites of an intolerable and disastrous social tyranny. There are no conditions of a fair trade, no equality of the two parties, in this fundamental exchange, in their hold on each other.

Ward, Lester F. 1888. Dynamic Sociology vol. I. D. Appleton and Co.: New York.

[509] It must necessarily follow that, wherever intelligence works evil, it is due to inequality of opportunity to acquire knowledge; and this constitutes a powerful argument for impartial education.

Lacy, George. 1888. Liberty and Law. Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co.: London.

[249-251] [The Collectivists’] position is based upon reason, and reason inculcates justice. But justice can never countenance any wanton or any avoidable suffering. … This then is Socialism. It is Justice, founded on Reason, and enforced by the power of the State. … It has no theory of the essential equality of all, such as W. H. Mallock, in his pretentious and wordy ‘Social Equality,’ wastes so many fine sentences, and so much sham logic, on in demolishing. On the contrary, it asserts the essential inequality of wants, desires, and possibilities in men, but at the same time declares that however great these inequalities may be, they can never warrant the leaving any one without the means of support, or justify the appropriation of the major portion of the good things of this world by a fortunate few whom circumstances have favoured. … [Socialists] declare that if all had the opportunity of showing the stuff that is in them they would rapidly rise into different positions, but they are effectually tied down by the restrictions that wealth imposes upon all those that have none. … The only equality the Socialist demands is equality of opportunity. And it does not demand this in the sham way that Individualism professes to grant it. Individualism verbally accords equality of opportunity, and then insists on conditions that make the grant worse than a mockery, absolutely nugatory. Socialism not only demands equality of opportunity, but it also insists that this should be enforced by the power of the State, and should be a real equality, not a sham one. Given this equality, most inequalities will disappear, in so far as they are of great extremes. … Therefore, while Socialism starts from the basis of the natural right of each to comfort, and the duty of each to work for it, it accords, in respect of the surplus, to each in accordance to his performance, always provided that his performance is for the general good, and not detrimental to it.

Denslow, Van Buren. 1888. Principles of the Economic Philosophy of Society, Government and Industry. Cassell and Co.: New York.

[172] For where, of two co-operative agents, neither can act without the other, both are equal, and being equal in efficiency should have equal pay. Again, a dollar to a rich man is exactly equal to a dollar to a poor man, in the sense that if a rich man renders a service worth a dollar, his right to the dollar is as good, in ethics and equity, as that of a poor man. If, therefore, he brings to the poor man a co-operative agent, viz. capital, with which the poor man is enabled to earn a dollar which he otherwise could not, he renders an equal service to that which the poor man renders to him, if the poor man so uses this capital as to cause it to earn a dollar for the capitalist, through capital which would otherwise earn less.

Owen, Albert Kimsey. 1890. Integral Co-Operation at Work. John W. Lovell Co.: New York.

[48-49] The Constitution of the United States says that ‘all men are born free and equal.’ This is false. Men were held as chattel slaves at the very time this fine sentence was coined. There has never been a day since it was signed when every woman and most of the men living under the said government were not slaves—slaves without a home to call their own, and whose products were taken, by law, with as little regard to giving an equivalent as if every path and road to market were held by armed brigands who demanded toll or life from every person who passed. How can we, as thinking beings, expect that a Constitution which is false to the laws of nature can be a firm foundation to build a republic upon? Our wiseacres, who are always inventing an excuse for their own chains, explain this to mean ‘free and equal before the law,’ and here we see the truth in the old adage, that ‘when one lie is told it takes ten lies to support it.’ Equality before the law forsooth! Do you think that there is any justice in ‘equality before the law’ where a man knowingly and designedly breaks the law—breaks the law that he may rob another and enrich himself—and a woman who has always been trampled upon and discriminated against by the law, and who has not been allowed to study the law, unknowingly and unwittingly, in an effort to assist a drunken husband, widows and orphans to beggary, young girls to hard work for life, and old men to suicide, because of their loss, is bound over to answer as ‘a thief’ before the law—a young-woman, who, to save a sick mother from starving, steals a loaf of bread, is caught in the act and brought before the court as ‘a thief’—do you think equity is any part of the justice which will deal with these two equally before the law? Do you think that a man who has lost both arms and one leg should be only ‘equal before the law’ with him who has all his limbs and much more than an average intelligence? Do you not think with me that Florida, in exempting her one-armed soldiers from State taxes, has a better idea of justice than our forefathers who made the dwarf and giant equal before the law? Do you not think, that when equity is thought of seriously, that the law will endeavor to build up the weak—to foster and assist, in an artificial way, the misfortunes of birth and previous conditions of servitude, so that well-intentioned and worthy people will not be handicapped for life by accidents over which they have no control? Why! jockeys [3] are more reasonable in their treatment of horses than our ‘statesmen’ are in their laws relating to fellow-beings—the jockeys handicap the well-bred and smart horses when those of less ability are to run in the same race; but our law-makers do just the opposite—they handicap those who are already, by circumstances, handicapped, and then insist that they shall compete in the race, ‘equal before the law,’ with the strong, experienced and swift, and that all the stakes shall go to the winner. … Of one thing be assured, a constitution which is based upon an injustice can only exist by injustice.

Graham, William. 1891. Socialism, New and Old. D. Appleton and Co.: New York.

[396-397] Further, it is a consequence from Mr. Spencer’s ‘Law of Equal Freedom,’ as Professor Sidgwick affirms, that there should be interference of the State to produce greater equalities of opportunity, without which the law of Equal Freedom is of little use to us. That law is that ‘every man has freedom to do all that he wills, provided that he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man.’ But what is the good of such freedom, when the monopoly of others, who have all the land, all the places, all the capital, all the credit, all the means of getting a chance of any of these, prevents its exercise? To make this law a Magna Charta for the human race requires, for the people of these countries at least, a certain amount of Government interference and of Government legislation, in addition to the voluntary virtues of individuals. There is no real freedom, any more than equality, or even equality of opportunity in our modern communities for the propertyless, and such must either be helped by the community, or remain slaves, or pariahs, or obtain a living by dishonest or infamous courses, and it is better that they should be helped by the State when young, by getting education at least, which will give them a chance of a career, or of getting an honest livelihood.

Bellamy, Edward. 1893. “Economic Equality,” The New Nation 3(17): 213.

[213]As political equality is the remedy for political tyranny, so is economic equality the only way of putting an end to the economic tyranny exercised by the few over the many through superiority of wealth…. Until economic equality shall give a basis to political equality, the latter is but a sham.

Ely, Richard T. 1894. Socialism. Thomas Y. Crowell and Co.: New York.

[16] The…idea of distributive justice, and that which seems now to prevail generally among the more active socialists, is equality of income…an equality of value.

Ritchie, David George. 1895. Natural Rights. Swan Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[255] As with the idea of equality in ethics and in religion, equality before the law means the membership of a great whole. Equality in political rights—in the suffrage and in eligibility to office—is a different matter.

[258] The claim of equality, in its widest sense, means the demand for equal opportunity—the carrtire oucerte aux talents. The result of such equality of opportunity will clearly be the very reverse of equality of social condition, if the law allows the transmission of property from parent to child, or even the accumulation of wealth by individuals. And thus, as has often been pointed out, the effect of the nearly complete triumph of the principles of 1789—the abolition of legal restrictions on free competition—has been to accentuate the difference between wealth and poverty. Equality in political rights, along with great inequalities in social condition, has laid bare ‘the social question’; which is no longer concealed, as it formerly was, behind the struggle for equality before the law and for equality in political rights. As in the case of liberty, our attention is called to the difference between ‘formal’ or ‘negative’ and ‘real’ or ‘positive’ equality. The abolition of legal restrictions on free competition allows the natural inequalities of human beings, in vigour of body and mind, to assert themselves.

[260] But the individualism, which asserts itself in the reaction against the old social system, seems to be too chaotic for humanity to rest in it; and the State can only secure the real well-being—I may add, the real liberty and equality (so far as these are socially useful ends)—of its citizens, by taking over the functions of which it deprives the family and performing them in a higher and better way. Is any State that yet exists anywhere prepared to do that, or fit to attempt it? Yet all modern States are consciously or unconsciously moving in that direction.

Gonner, Edward Carter Kersey. 1895. The Socialist State: Its Nature, State, and Conditions. Walter Scott: London.

[23] While undertaking the positions of Industrial employer, landowner, and capitalist, the Socialist State will not surrender those other functions relating to the performance of Social Duties, which are to some extent or other performed by most modern governments. Health, Security, and Education will remain objects of its watchful care. The extension, not the relaxation, of measures on their behalf is rather to be anticipated. The revenue which will accrue from its new industrial position should supply means for far greater social undertakings than have been hitherto possible, and these will be in the direction of ‘greater equality of opportunities,’ to borrow a favourite expression. The probability of such a development has led many Socialists to represent ‘equality of opportunity’ as a measure in the social programme second only to collective organisation of industry. In reality, it is a feature which it possesses in common with all governments which have developed a social policy; though, in respect of its attainment, it offers the great advantage of an additional revenue composed of rent, interest, and industrial profits.

Ball, Sidney. 1896. “Moral Aspects of Socialism,” The International Journal of Ethics 6(3): 290-322.

[294] [Modern Scientific Socialism] is not concerned about the inequality of property, except so far as it conflicts with " equality of opportunity" or " equality of consideration" for all social workers…

Hammond, J. Lawrence. 1897. “A Liberal View of Education” in Essays in Liberalism by Six Oxford Men. Cassell and Co.: London.

[176] This conception of the State again underlies the great Liberal principles of freedom and equality of opportunity. The State makes freedom possible primarily by removing certain restraints upon development, which yield to an ordered form of cooperation. Equality of opportunity can only be recognised as the basis of equitable relations by men who acknowledge a common interest.

Brown, John. 1897. Parasitic Wealth. Charles H. Kerr and Co.: Chicago.

[11] Applying deductively the test of ethics to the social problem, we should consider that system of society the best which while conceding to the individual the greatest possible personal freedom consistent with the highest welfare of society as a whole, guarantees to every member of the community an equal chance in the race of life without prejudice, an equal opportunity without favor or hindrance.

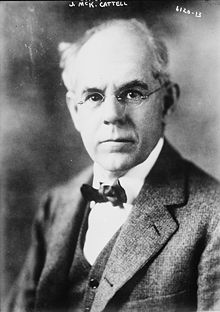

Franklin Henry Giddings (1855 – 1931) was an American sociologist and economist. For ten years, he wrote items for the Springfield, Massachusetts Republican and the Daily Union. In 1888 he was appointed lecturer in political science at Bryn Mawr College; in 1894 he became professor of sociology at Columbia University. From 1892 to 1905 he was a vice president of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Giddings, Franklin Henry. 1898. Elements of Sociology. The Macmillan Co.: New York.

[327-328] As was there shown, liberty in any sense, including that which democracy implies, is possible only if there is in the population a good degree of mental and moral homogeneity and of sympathy — a fact which is popularly expressed by the word ‘fraternity.’ … But, as we also know, there can be such brotherhood only if a certain approach towards equality of condition is secured. In the historical evolution of human society, nothing has proved to be more fatal to the spirit of brotherhood and to the maintenance of liberty than an unchecked growth of inequality in material conditions, possessions, and power. These modes of equality can be approximately established by the perfection of an efficient system of public school education, but not by any other means. Finally, there must be maintained also that mode of equality on which progress depends; namely, equality of opportunity for potential inventiveness, greatness, and leadership to become actual.

Ritchie, David George. 1900. “Evolution and Democracy” in Ethical Democracy edited by Stanton Coit. Grant Richards: London.

[3] If progress depends upon a perpetual struggle for existence, there seems indeed a prima facie argument for liberty in the negative sense of laissez-faire; but everything else that may be included in democratic ideals appears to be condemned as hopeless or mischievous in its consequences. Nature produces not equality but inequality; nay, inequality is even requisite for natural selection to work upon.

Hobson, John Atkinson. 1900. “The Ethics of Industrialism” in Ethical Democracy edited by Stanton Coit. Grant Richards: London.

[94] Genuine economic reform of business life will never be possible until the public intelligence has grasped this central fact, that competition and bargain are essentially unfair, and therefore are socially injurious modes of determining the prices of all things sold. There exists no security for equality of gain in any bargain.

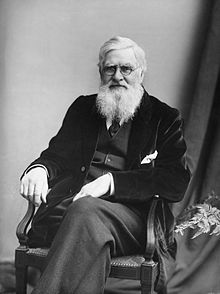

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 – 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, and biologist. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural selection; his paper on the subject was jointly published with some of Charles Darwin's writings in 1858. This prompted Darwin to publish his own ideas in On the Origin of Species.

Wallace, Alfred. 1900. Studies Scientific and Social. Macmillan and Co.: London.

[513] In our present society the bulk of the people have no opportunity for the full development of all their powers and capacities, while others who have the opportunity have no sufficient inducement to do so. The accumulation of wealth is now mainly effected by the misdirected energy of competing individuals; and the power that wealth so obtained gives them is often used for purposes which are hurtful to the nation. There can be no true individualism, no fair competition, without equality of opportunity for all. This alone is social justice, and by this alone can the best that is in each nation be developed and utilized for the benefit of all its citizens. I propose, therefore, to state briefly what is the ethical foundation for this principle, and what its practical application implies.

[516] Equality of Opportunity is absolute fair play as between man and man in the struggle for existence. It means that all shall have the best education they are capable of receiving; that their faculties shall all be well trained, and their whole nature obtain the fullest moral, intellectual, and physical development.

[517] It is here that most people (including Herbert Spencer and Mr. Kidd) object to the application of the principle that every man shall receive the results of his own nature and conduct, or, in other words, shall have ‘equality of opportunity,’ as being unjust or injurious. But if this principle is the essential feature of social justice, its full application cannot be unjust; while if it is the true correlative in human society of survival of the fittest among the lower forms of life, it cannot be injurious.

[517] And it is still more obvious, that a society which has adopted the principle of equality of opportunity as the only means of securing true individualism and competition under fair and equal conditions, may justly prevent individuals from introducing inequality by their injudicious gifts or bequests.

[520] I submit, therefore, that the adoption of the principle of Equality of Opportunity as our guide in all future legislation, should be acceptable to every social reformer who believes in the supremacy of Justice. To the individualist it would mean the fullest application of his principle of individual freedom limited only by the like freedom of others, since this principle is a mere mockery under the present negation of fair and equal conditions to the bulk of the citizens of all civilized states. And it should be equally acceptable to the socialist, because the greatest obstacle to his teachings would be removed by the abolition of ignorance and of that grinding poverty and want which leaves no time or energy for any struggle but that for bare existence. Equality of Opportunity, founded as it is upon simple Justice between man and man, is therefore well fitted to become the watchword of the social reformers of the Twentieth Century.

Watt, Wellstood Alexander. 1901. A Study of Social Morality. T. and T. Clark: Edinburgh.

[11-12] Again, the demand for equality may be widened to one for social equality—an equality of social recognition. This conception in itself is somewhat ambiguous. It may, however, define itself by taking the form of a claim for equal economic opportunity, and for laws which are equal in the sense that they will, so far as possible, secure that end. Or it may take the form of a demand for equal social conditions, which are to be permanently preserved in spite of the tension that tends to upset them. We thus arrive at far reaching assertions of principle which are not easily discussed in a few words. But equality, as an abstract conception which can prima facie be admitted to be reasonable, probably resolves itself into a claim for social adjustment in view of the fact of the rational nature of the members of the community. It represents the common rationality of men. Such a claim may in turn be extended to a demand for proper relations among all mankind viewed as possible members of a rational society. The formal element of equality, then, though somewhat vague, is based on a primary social fact; and, at anyrate[4] , tends to break down artificial restrictions when they are seen to be such.

Addams, Jane. 1902. Democracy and Social Ethics. Macmillan Co.: New York.

[178-179] Just as we have come to resent all hindrances which keep us from untrammelled comradeship with our fellows, and as we throw down unnatural divisions, not in the spirit of the eighteenth- century reformers, but in the spirit of those to whom social equality has become a necessity for further social development, so we are impatient to use the dynamic power residing in the mass of men, and demand that the educator free that power. We believe that man's moral idealism is the constructive force of progress, as it has always been; but because every human being is a creative agent and a possible generator of fine enthusiasm, we are sceptical of the moral idealism of the few and demand the education of the many, that there may be greater freedom, strength, and subtilty of intercourse and hence an increase of dynamic power.

Ely, Richard T. 1903. Studies in the Evolution of Industrial Society. The Macmillan Co.: New York.

[420] Another line of development in the interests of industrial liberty must consist in opening up and increasing opportunities for the acquisition of a livelihood by the mass of men, in order that back of contracts there may lie a nearer approximation to equality of strength on the part of two contracting parties. It is certain that there will be a vast development along this line during the twentieth century, and through this development we shall find liberty expressing itself increasingly through contract.

Walter Thomas Mills (1856–1942) was an American socialist activist, educator, lecturer, writer, and newspaper publisher. He is best remembered for the role he played in the Socialist Party of America during the first decade of the 20th century as one of the leaders of the organization's moderate wing.

Mills, Walter Thomas. 1904. The Struggle for Existence, fifth ed. International School of Social Economy: Chicago.

[311] Economic Justice: The capitalist assumes that under competition all men and women will be able to secure what is just, and so provide for the highest welfare for each to which he can be justly entitled. The answer is that if the parties to the competition were exact equals in strength, skill and good fortune, they might be able to exactly neutralize each other's efforts to serve society while striving with each other, but so long as any share of their strength is expended contending with each other, the largest production cannot be realized. It was the inequality of strength, skill and good fortune in war which made the coming of capitalism possible in the first place. Competition between the weak and the strong does not mean the welfare of both; it means the sweat-shop for the helpless and leisure and luxury for the strong. Socialism demands that the strength of society be used to perpetually maintain equal opportunities for those unequally endowed, in order that all may live. Capitalism demands unequal opportunities for those unequally endowed, and the inequality of opportunity which it enforces is against those who are weak and in behalf of those who are strong.

Ritchie, David George. 1905. Philosophical Studies. Macmillan and Co.: London.

[336] It is not true that any and every human being is equal to any other. But the democratic ideal is that, as far as outward arrangements go, they ought to be equal.

[338] The true defence of democracy, i.e. of equality of political and then of social opportunity, is that human beings are not equal in capacities or in character, but that their respective merits can only be ascertained by actual trial. Judged from the standard of society as an organism, and not as an aggregate of individuals gifted with equal natural rights, democratic institutions are defensible in so far as they offer (or can be made to offer) the best means of obtaining a genuine aristocracy or government by the best.

Hobhouse, Leonard T. 1905. Democracy and Reaction. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[217] [The labourer] is not free in making his bargain because he is not equal to the [capitalist], and the object of the law is to obtain for him conditions on which, if he were free and equal, he would, it is held, insist.

[219-221] So far, then, it appears that what seem on the surface to be the main departures from the principles of liberty and equality, which have commanded the approval of the average modern Liberal, are in reality departures by which the principles of liberty and equality are developed and extended. It results that the breach of principle between the Liberalism of Cobden’s time and the Liberalism of to-day is much smaller that appears upon the surface. … Men of Cobden’s time…[had] the habit of looking upon Government as an alien power, intruding itself from without upon the lives of the governed. We, on the contrary, habituated by the experience of a generation to looking upon Government as the organ of the governed, begin to find even the phrases of Cobden’s time unfamiliar and inexact expression of the facts…. The change which has taken place in the minds of popular statesmen since Cobden’s day is due to the realization of the democratic principles for which the men of Cobden’s time fought.

Seligman, Edwin Robert Anderson. 1905. Principles of Economics. Longmans, Green and Co.: New York.

[163] Economic freedom, like all liberty, is not an attribute of primitive man, but has been hammered out by centuries of toilsome effort. Individual liberty is the product of social effort. If it is to be a constructive rather than a destructive force, if it is to minister to social progress rather than to social dissolution, it must be accompanied by two other conditions. Of these the first is equality. By equality we do not mean absolute equality. … Men are born with an inequality of physical, mental and moral attributes which no amount of care can eradicate; and as soon as private property develops, these natural inequalities inevitably produce their results in inequality of possessions.

[164] The real equality that is important for economic purposes is threefold: first, legal equality, or the certainty that one man is as good as another before the law, and that his economic rights will be equally protected; secondly, equality of opportunity, in the sense that no man is shut out by legislation or social prejudice from free access to any vocation or employment for which he deems himself fitted; thirdly, such a relative equality, at least in the conditions of bargaining, as not to put one party to the contract at the virtual mercy of the other. Without such a threefold equality freedom becomes illusory; for liberty based on gross inequality means the liberty of the stronger and more unscrupulous to impose his will on the weak. Liberty without equality is the power of the one, but the subjection of the other. The liberty to invest one's capital in slaves was stoutly defended by the ante-bellum Southerner, but his liberty involved the other’s slavery.

Ward, Lester Frank. 1906. Applied Sociology. Ginn and Co.: Boston.

[281] There is no use in talking about the equalization of wealth. Much of the discussion about ‘equal rights’ is utterly hollow. All the ado made over the system of contract is surcharged with fallacy. There can be no equality and no justice, not to speak of equity, so long as society is composed of members, equally endowed by nature, a few of whom only possess the social heritage of truth and ideas resulting from the laborious investigations and profound meditations of all past ages, while the great mass are shut out from all the light that human achievement has shed upon the world. The equalization of opportunity means the equalization of intelligence, and not until this is attained is there any virtue or any hope in schemes for the equalization of the material resources of society.

Lloyd, Henry Demarest. 1906. Man, the Social Creator. Doubleday, Page, and Co.: London.

[70] To develop to the fullest his faculty for the service of life, including himself, is the highest duty and privilege of the individual, and to get for all and each the benefit of this individual development is the highest function of society. The establishment of this freedom of opportunity is called Social Equality, and its object is to encourage the growth of every variety of faculty. Social Equality exists to stimulate individual inequality. This social function requires social action. This has been made possible by the invention of the state. But the state is now passing through a crisis of its own, and is temporarily unable to expand with the needs of this social function for expansion. Parliamentary Government, Talk Government, Government by party selfishness, is visibly breaking down. Government by politics, changing policies and administrators with every change in the public mood or in the schemes of clique greed, is proving self-destructive. The task of the Labour movement is forcing the reorganisation of the state on lines more nearly parallel with those of human and social development.

John Spargo. 1909. Socialism: A Summary and Interpretation of Socialist Principles. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[314-315] When too many laborers rush into certain branches of industry, the natural way to lessen their number and to increase the number of laborers in other branches where there is need for them, will be to reduce wages in the one and to increase them in the other. Socialism, instead of being denned as an attempt to make men equal, might perhaps be more justly and accurately denned as a social system based upon the natural inequalities of mankind. Not human equality, but equality of opportunity, and the prevention of the creation of artificial inequalities by privilege, is the essence of Socialism.

Hobson, John Atkinson. [1909] 1974. The Crisis of Liberalism. Harper and Row Publishers: New York.

[87] A true Democracy is only possible when Society, a true organism, becomes conscious in its intelligence and will, and thus capable of that self-control which is the essence of Democracy, and which contains the only liberty and equality that are worth the names.

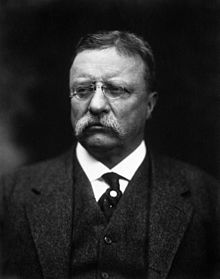

Theodore "T.R." Roosevelt, Jr. (1858 – 1919) was the 26th President of the United States (1901–1909). He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity. He was a leader of the Republican Party and founder of the first incarnation of the short-lived Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party of 1912, which put Woodrow Wilson into office. Before becoming President, he held offices at the city, state, and federal levels.

Roosevelt, Theodore. 1910. The New Nationalism. The Outlook Company: New York.

[178] Our republic has no justification unless it is a genuine democracy — a democracy economically as well as politically — a democracy in which there is a really sincere effort to realize the ideal of equality of opportunity for all men. And there can be no such equality of opportunity if a man is either helped by special privilege or hampered by the special privileges which others have. Now, one way to secure such equality of opportunity is, so far as possible, to give equality of start. In other words, give the full-grown man, the full-grown woman, who starts in life to make his or her way according to the abilities given to him or her, as good a chance as we are able to give them. That means that it is our duty to provide such means of education as will enable each man to become a self-respecting unit in the community.

Jovner, James V. 1910. “Some Dominant Tendencies in American Education,” (NEA) Journal of the Proceedings and Addresses (July 2-8): 78-92.

[79] The thoughtful student may easily discern a few potent and permanent tendencies in American education. The greatest good to the greatest number and equality of opportunity to all are fundamental principles of democracy. One logical demand of democracy, therefore, is a system of education that shall provide equality of educational opportunity for all, and that shall best fit each for the greatest service to the greatest number. Out of this logical demand of democracy has grown the demand for industrial or vocational education.

[79-80] With the growth of the democratic spirit, the recognition of the civil and religious rights of the common man, there dawned a new era of liberty on earth. The common man has slowly come to understand that there is no liberty without learning, no equality of opportunity without equality of educational opportunity, guaranteeing to every child, as an inherent right, the chance to develop to the fullest every power in him for effective service.

With this new conception of his educational rights, the common man first demanded an equal chance for his child to obtain the same sort of education that the favored few alone had heretofore enjoyed. In obedience to this demand, a system of free elementary schools was first established, furnishing equality of opportunity to the children of the rich and the poor, the high and the low, alike, to obtain therein the essentials of intelligence.

MacDonald, James Ramsay. 1911. The Socialist Movement. Henry Holt: New York.

[139] What do Socialists mean by equality? They mean that the inequalities in the tastes, the powers, the capacities of men may have some chance of having a natural outlet, so that they may each have an opportunity to contribute their appropriate services to society. … Consequently, the purpose is generally stated as being to secure ‘equality of opportunity.’

[140] Nobody misunderstands Socialism so courageously as Mr. Mallock [in A Critical Examination of Socialism], and I refer to his argument in order to make the Socialist idea clear. He says that the idea is purely abstract and has to be brought down into touch with actuality. And this is how he does it. It implies, he says, that at the beginning of industrial life all should start at the same place and in the same path. That is absurd. If two boys start German together, he argues, one will learn faster than the other, and therefore there is no equality of opportunity between them. Which again is absurd, for the equal start is the equality asked for. His third point is that under Socialism an employee of a state factory would have no more equality of opportunity than an employee of a private concern. Whether he has or has not may be a debatable point, but as I shall try to show in my next chapter Socialist industrial organisation will allow the best men the widest scope of usefulness which can only be secured by equal opportunities for those who run equal up to the point of entering industrial life.

Hobhouse, Leonard T. [1911] 1994. Liberalism and Other Essays. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA.

[15] “Once more the struggle for liberty is also, when pushed through, a struggle for equality. Freedom to choose and follow an occupation, if it is to become fully effective, means equality with others in the opportunities for following such occupation. This is, in fact, one among the various considerations which lead Liberalism to support a national system of free education….”

[18] …[T]he function of Liberalism may be rather to protect the individual against the power of association than to protect the right of association against the restriction of the law. In fact, in this regard, the principle of liberty cuts both ways, and its double application is reflected in history…. It was again, a movement to liberty through equality. … Upon the whole it may be said that the function of Liberalism is not so much to maintain a general right of free association as to define the right in each case in such terms as make for the maximum of real liberty and equality.

[40] In the matter of contract true freedom postulates substantial equality between the parties.

[43] True consent is free consent, and full freedom of consent implies equality on the part of both parties to the bargain. Just as government first secured the elements of freedom for all when it prevented the physically stronger man from slaying…his neighbors, so it secures a larger measure of freedom for all by every restriction which it imposes with a view to preventing one man from making use of any of his advantages to the disadvantages of others.

[58] [The] sense of ultimate oneness is the real meaning of equality, as it is the foundation of social solidarity and the bond which, if genuinely experienced, resists the disruptive force of all conflict….

Bonar, James. 1911. Disturbing Elements in the Study and Teaching of Political Economy. John Hopkins Press: Baltimore.

[11-12] Economically, Ricardo, James Mill, and J. R. MacCulloch are representatives of this school of economists. Their emphasis lies on the equality (or identity) of the economic units. … Those men undoubtedly include in their programme the liberty advocated by Adam Smith; they are political reformers in this sense also. But the claim for equality was less generally conceded, and therefore they insist on it more. The equality is like Adam Smith’s liberty, negative in character. Remove obstructions and men are free; remove their differences they are equal. … It meant the survival of the economically strongest among those all equally competitors but not at all equal in the competition. This would be true even where the liberty in the negative sense was perfect, a state of things never realized, though more nearly approached now than formerly. The men who from the first felt the inadequacy of the negative idea both of liberty and equality were the social reformers.

[17] Our present notion of liberty, that has been gradually forming itself in the last twenty-five years, is of the command of opportunity for development rather than the confronting of a cleared course where all obstacles are removed. It is positive, not simply negative. In the same way our notion of equality is of equal opportunity.

William English Walling (1877–1936) was an American labor reformer and Socialist Republican. He was the grandson of William Hayden English, the Democratic candidate for vice president in 1880, and was born into wealth. He was educated at the University of Chicago and at Harvard Law School. He was a co-founder of the NAACP, and founded the National Women's Trade Union League in 1903.

Walling, William English. 1912. Socialism as it Is. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[98] The definite establishment of industrial capitalism, a century or more ago, and later the settlement of new countries, brought about a revolutionary advance towards equality of opportunity. But the further development of capitalism has been marked by steady retrogression. Yet nearly all capitalist statesmen, some of them honestly, insist that equality of opportunity is their goal, and that we are making or that we are about to make great strides in that direction. Not only is the establishment of equality of opportunity accepted as the aim that must underlie all our institutions, even by conservatives like President Taft, but it is agreed that it is a perfectly definite principle. Nobody claims that there is any vagueness about it, as there is said to be about the demand for political, economic, or social equality.

[98-99] It may be that the economic positions in society occupied by men and women who have now reached maturity are already to some slight degree distributed according to relative fitness; and, even though this fitness is due, not to native superiority, but to unfair advantages and unequal opportunity, it may be that a general change for the better is here impossible until a new generation has appeared. But there is no reason, except the opposition of parents who want privileges for their children, why every child in every civilized country to-day should not be guaranteed by the community an equal opportunity in public education and an equal chance for promotion in the public or semi-public service, which soon promises to employ a large part if not the majority of the community.

Bax, Ernest Belfort. 1912. Problems of Men, Minds, and Morals. Small, Maynard, and Co.: Boston.

[156-157] Equality, understanding by the term social and economic Equality, is a condition of the universality of real Liberty, and Equality in any other sense is a chimera. Differences of temperament, of ability, and of character generally, must exist, but these are not incompatible with the most complete political and economic Equality. This Equality, based as it is on equal economic advantage and equal economic opportunity, is the Equality demanded by Socialism. This Equality, it need scarcely be said, in no way implies any dead level of mediocrity, such as haunts the imaginations of so many critics of Socialism. On the contrary, as I have elsewhere shown, it is the system of Capitalism which produces, and must necessarily produce, the dead level spoken of, a state of things which would be completely changed by Socialism. If to real Equality, Liberty in the three forms we have above discussed is necessary, it is no less true that to the full fruition of all forms of Liberty, Equality in the sense we have just indicated is equally essential. You cannot fully realise the one without the other.

Bellamy, Edward. 1913. Equality. Appleton and Company: New York.

[79] There is another great and equal right of all men which, though strictly included under the right to life, is by generous minds set even above it: I mean the right of liberty—that is to say, the right not only to live, but to live in personal independence of one’s fellows, owning only those common social obligations resting on all alike.

[86] As it seems to us, the offense of the old order against liberty was even greater than the offense to life; and even if it were conceivable that it could have satisfied the right of life by guaranteeing abundance to all, it must just the same have been destroyed, for, although the collective administration of the economic system had been unnecessary to guarantee life, there could be no such thing as liberty so long as by the effect of inequalities of wealth and the private control of the means of production the opportunity of men to obtain the means of subsistence depended on the will of other men.

McClenon, Walter Holbrook. 1914. A Compromise with Socialism. Los Angeles, CA.

[28] But altho it is not necessary or desirable to reduce all individuals to the dead level of a common uniformity, it is, as we have said, absolutely necessary for us to recognize the principle of equality of opportunity. There have not been wanting examples of the application of this principle in specific situations. It is this principle that has furnished the demand for laws against rebates and other forms of railway discriminations, and which lies at the basis of all social legislation, especially laws relating to housing conditions. In fact, there is scarcely any province of law in which we do not find important applications of the rule that equal opportunity is to be given to all citizens, without discrimination on account of extraneous considerations. … In fact, it would scarcely be an exaggeration to say that this principle is at the foundation of every one of the specific proposals that we have to offer as a solution of the social and industrial problems of the present day. There is a wide field in which it is possible to secure equality of opportunity without tending to reduce all persons to a common level of mediocrity. Especially is this true in the matter of education.

Hobson, John Atkinson. 1914. Work and Wealth. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[165] Equality of opportunity does not imply equality but some inequality of incomes. For opportunity does not consist in the mere presence of something which a man can use, irrespective of his own desires and capacities. A banquet does not present the same amount of opportunity to a full man as to a hungry man, to an invalid as to a robust digestion. £1,000, spent in library equipment for university students, represents far more effective opportunity than the same sum spent on library equipment in a community where few can read or care to read any book worth reading. Equality of opportunity involves the distribution of income according to capacity to use it, and to assume an absolute equality of such capacity is absurd.

Walling, William English. 1914. Progressivism—And After. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[53-54] Equality of opportunity is a well-worn phrase, and Wilson would be justified in using it in its older and looser sense. … If strictly and literally employed, however, equality of opportunity (as I shall point out) means, not merely the elimination of labor waste, but Socialism. And, moreover, when employed, as in the present instance, in immediate and explicit connection with the labor question, it can only mean this real equality of opportunity—that is equality of opportunity for all, including labor, and not merely equality of opportunity for those having the capital required for initiating successful commercial undertakings—or in lieu of capital the extremely exceptional ability which alone can replace capital in view of the extremely overcrowded condition of all commercial occupations to-day. Wilson here gives us distinctly to understand that, if men are shielded in their ‘lives’ and ‘vitality,’ this real equality of opportunity will result. Yet, if we search the President's writings as to how this will come about, we find that he restricts his plans looking toward equality of opportunity entirely to the commercial form.

Laughlin, James Laurence. 1915. “Business and Democracy,” The Atlantic Monthly 116(1): 89-98.

[98] Meanwhile, every means should be used to further equality in industry. It should be the aim of every one to see that those of equal capacities should have, as nearly as possible, equal rewards. In the actual whirl of busy production this may not always be so; and our business men are in duty bound to see that there is no cause for complaint on the score of a desire to get profits at the expense of another human being. The rich and successful are under a moral obligation to the poor and unsuccessful. Much may be done to show the workmen that they are regarded, not as machines to earn profit, but as human beings to be given greater comfort and happiness. In the sense of equal wages for equal capacities, industrial democracy can hope for industrial equality.

Nearing, Scott. 1916. Poverty and Riches. The John C. Winston Co.: Philadelphia.

[232] Equality of opportunity is the germ thought of democracy. … The Industrial Regime, the dominating force in modern life, must stand trial on all of the issues of democracy, but, most important of all, it must provide equal opportunity for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Parmelee, Maurice. 1916. Poverty and Social Progress. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[422] But these differences in human talent do not preclude the possibility and certainly do not negate the desirability of equality of opportunity. That is to say, this diversity does not prevent the possibility of each individual having an opportunity equal to that of every one else to make the best use of his capacity, and to lead a normal human existence as far as it is possible for him to do so. Equality of opportunity is, therefore, the first and foremost object and condition of democracy, and in a sense includes all the rest. And that this is of immediate significance for the prevention of poverty must be evident, when we consider that many of the poor would not be in poverty if they had the opportunity to produce what they are capable of producing, or could retain possession of what they do produce.

In the second place, we have already seen in our first chapter that any form of organization of society involves a certain amount of restriction upon the liberty of the individual. But we have recognized that such restriction is a necessary evil, which should be tolerated only to the extent that it is essential for the organization of society; because the attainment of the highest possible degree of personal liberty is one of the ends of democracy. This must be so, in the first place, in order to have the equality of opportunity which we have already postulated as the first end of democracy.

Sellars, Roy Wood. 1916. The Next Step in Democracy. The Macmillan Company: New York.

[194-195] Certain general reforms suggest themselves at once. These have been grouped together frequently enough under the caption, equality of opportunity. Equality of opportunity, it is asserted, will give the conditions for a fairer competition between individuals for rewards. Eliminate the obviously unfit by kindly segregation, prevent the propagation of those who are sub-normal by similar measures; distribute the burdens of accident and unemployment over society as a whole instead of letting them fall upon the individual or the family; better the opportunity for an education suited to the nature of the individual and the role he will probably play when he grows up. All these reforms will lead to a healthier society and one in which the individual is more capable of competing with his fellows. Besides, such individuals will be more apt to cooperate together for the development of socialized institutions and methods.

Stevens, Ernest Guy. 1917. Civilized Commercialism. E. P. Dutton and Company: New York.

[150] The interest of society as a whole should be placed before the interest of any part. Even sellers are buyers. Under a system of equal justice the equal freedom of all must be preferred to the privilege of some. A present commercial adjustment which is resulting in commercial privilege therefore needs readjustment. A system which is working inequality of opportunity needs to be readjusted until it works equality of opportunity. As only further inequality can be reached by further adjusting our commercial system in the interest of sellers, it is time to adjust it in the interest of buyers.

[151-152] The present system attempts to reach equality of opportunity by in theory giving all, as sellers, an equal opportunity to prey. The opportunity, for most, is barren because its philosophical basis is false. … To the great majority of our people equality of economic opportunity is not now open. The chief reason is that the present system of buying and selling benefits sellers at the expense of buyers. The present system has allowed monopoly to raise prices over the country and reduce them below cost in some small town to kill off a competitor there or keep him from getting a start. The small competitor has thus lacked an equal opportunity. But it has only been possible for the trust to destroy him unfairly because it has been free to close equality of economic opportunity to buyers over the rest of the country. They were denied the opportunity to buy on equal terms with those in the small town. Buyers in the country at large have thus paid, unjustly, the cost of unjustly crushing competition and supinely allowed an evil system to continue which works against themselves to their own great loss, both present and future.

Tufts, James Hayden. 1918. Our Democracy. Henry Holt: New York.

[282-283] Equal opportunity is the necessary condition for progress—to get the benefit of prizes and honors we must first have equal opportunity. Just as in the race true honor comes from winning against those who are well-trained and thoroughly ‘fit,’ so in life true honor comes from winning where every one has a fair chance. Inequality is of benefit only if we first have equality of opportunity.

Husslein, Joseph Casper. 1918. The World Problem. P. J. Kennedy and Sons: New York.

[33] The fantastic doctrine of equality, in defiance of nature and nature’s God, has largely given way in Socialist circles to the demand for an equality of opportunity. But where has there ever been such equality of opportunity as within the Church herself, where the most despised slave might attain to the honors of the chair of Peter, and more than once had actually done so in the past, while men from every rank and class have in modern times governed the Church of God? There is no measure of equality of opportunity, within right reason and the law of God, that the Catholic Church will not gladly bless and approve.

Adams, Henry Carter. 1918. Description of Industry. Henry Holt: New York.

[45] Equality of Opportunity. It lies in the theory of industrial law that all men shall be granted the same opportunity of industrial success. This is attained by the abolition of classes, so far as classes are recognized by law. In the modern world, no legal privilege is conferred by the accident of birth. There are no industrial rules which limit men in their choice of a place in industry. Every profession, trade, or line of business, opens its doors to the choice of industrial freemen. A son is no longer limited to the industrial station which his father occupied. On the contrary, it is assumed by the legal system under which we live that every avenue of work is open to every man, and that he has the choice to make good or to fail in any profession, trade, or line of business that he chooses.

The industrial theory which springs out of this fact of law is that, through freedom of opportunity, society as well as individual workers will reap the highest possible benefits. It assumes that, under equal opportunity, every worker will do the best possible for himself, and that in so doing he will contribute in the highest degree possible to the well-being of all workers. The legal framework of modern industry places no barrier to the highest success which it is possible for any citizen of the business world to attain.

Roosevelt, Theodore. 1919. Newer Roosevelt Messages, Vol. III edited by William Griffith. The Current Literature Publishing Co.: New York.

[811] We should do everything that can be done, by law or otherwise, to keep the avenues of occupation, of employment, of work, of interest, so open that there shall be, so far as it is humanly possible to achieve it, a measurable equality of opportunity; an equality of opportunity for each man to show the stuff that is in him. We ought, as far as possible, to make it possible for each man to obtain the education, the training which will enable him to take advantage of the opportunity, if he has the stuff in him to do so. When it comes to reward, let each man, within the limits set by a sound and far-sighted morality, get what, by his energy, intelligence, thrift, courage, he is able to get, with the opportunity open. We must set our faces against privilege; just as much against the kind of privilege which would let the shiftless and lazy laborer take what his brother has earned as against the privilege which allows the huge capitalist to take toll to which he is not entitled. We stand for equality of opportunity, but not for equality of reward unless there is also equality of service. If the service is equal, let the reward be equal; but let the reward depend on the service; and, mankind being composed as it is, there will be inequality of service for a long time to come, no matter how great the quality of opportunity may be; and just so long as there is inequality of service it is eminently desirable that there should be inequality of reward.

Sir Halford John Mackinder (1861 – 1947) was an English geographer, academic, the first Principal of University Extension College, Reading (which became the University of Reading) and Director of the London School of Economics. He is regarded as one of the founding fathers of both geopolitics and geostrategy.

Mackinder, Halford John. 1919. Democratic Ideals and Reality. Henry Holt: New York.

[233] Now the expression ‘Equality of Opportunity’ involves two things. In the first place control, because, given average human nature, there cannot be equality without control; and in the second place it implies freedom to do and not merely to think, or, in other words, opportunity to bring ideas to the test of action. Mr. Bernard Shaw says that ‘He who can, does; he who cannot, teaches.’ If you interpret the words ‘can’ and ‘cannot’ as implying opportunity and lack of opportunity, then this rather cynical epigram conveys a vital truth.

Myers, William Starr. 1919. Socialism and American Ideals. Princeton University Press: Princeton.